Key information

Publication type: The London Plan

Publication status: Adopted

Publication date:

Contents

Policy HC1 Heritage conservation and growth

7.1.1 London’s historic environment, represented in its built form, landscape heritage and archaeology, provides a depth of character that benefits the city’s economy, culture and quality of life. The built environment, combined with its historic landscapes, provides a unique sense of place, whilst layers of architectural history provide an environment that is of local, national and international value. London’s heritage assets and historic environment are irreplaceable and an essential part of what makes London a vibrant and successful city, and their effective management is a fundamental component of achieving good growth. The Mayor will develop a London-wide Heritage Strategy, together with Historic England and other partners, to support the capital’s heritage and the delivery of heritage-led growth.

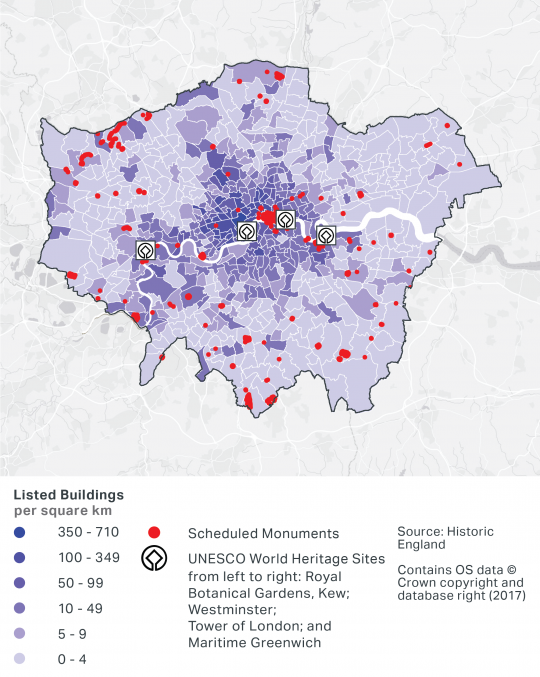

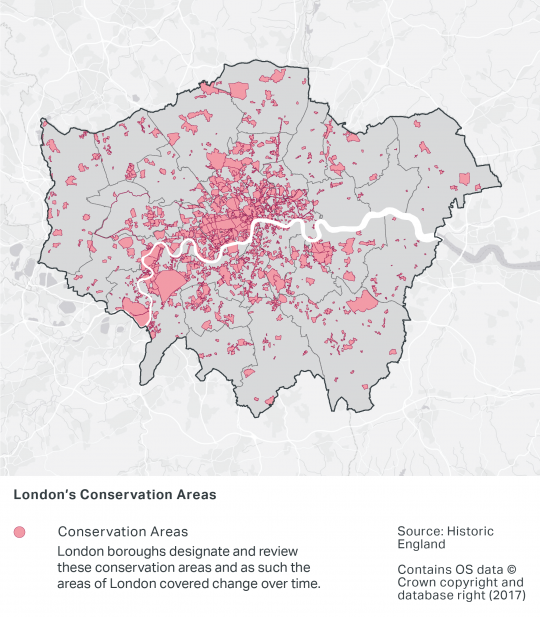

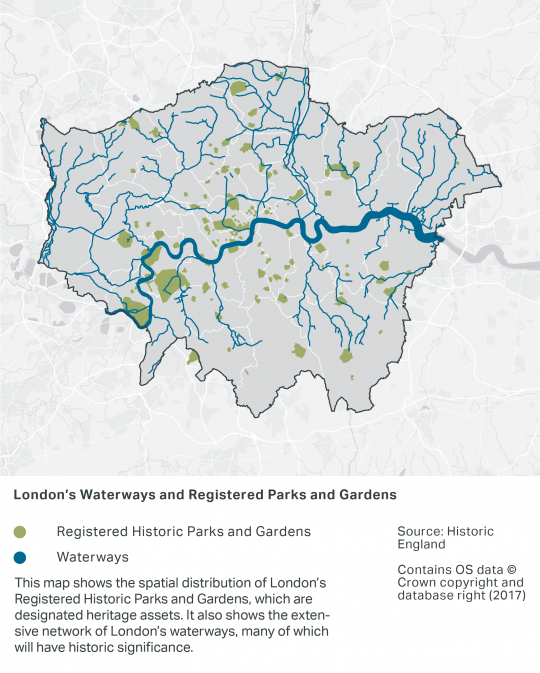

7.1.2 London’s diverse range of designated and non-designated heritage assets contributes to its status as a world-class city. Designated assets currently include four World Heritage Sites, over 1,000 conservation areas, 19,000 list entries for historic buildings, 150 registered parks and gardens, 160 scheduled monuments, and one battlefield. Non-designated assets cover an even wider range of features including buildings of local interest, most archaeological remains, canals, docks and waterways, historic hedgerows, ancient woodlands, and ancient and veteran trees. The distribution of designated assets differs across different parts of London, and is shown in Figure 7.1, Figure 7.2, Figure 7.3, and Figure 7.4. Note that these maps are for illustrative purposes only.

Figure 7.1 - Listed Buildings, Scheduled Monuments and World Heritage Sites

Figure 7.2 - London’s Conservation Areas

Figure 7.3 - London’s Waterways and Registered Historic Parks & Gardens

7.1.3 Ensuring the identification and sensitive management of London’s heritage assets, in tandem with promotion of the highest standards of architecture, will be essential to maintaining the blend of old and new that contributes to the capital’s unique character. London’s heritage reflects the city’s diversity, its people and their impact on its structure. When assessing the significance of heritage assets, it is important to appreciate the influence of past human cultural activity from all sections of London’s diverse community. Every opportunity to bring the story of London to people and improve the accessibility and maintenance of London’s heritage should be exploited. Supporting infrastructure and visitor facilities may be required to improve access and enhance appreciation of London’s heritage assets.

7.1.4 Many heritage assets make a significant contribution to local character which should be sustained and enhanced. The Greater London Historic Environment Record (GLHER)[127] is a comprehensive and dynamic resource for the historic environment of London containing over 196,000 entries. In addition to utilising this record, boroughs’ existing evidence bases, including character appraisals, conservation plans and local lists should be used as a reference point for plan-making and when informing development proposals.

7.1.5 As set out in Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth, Development Plans and strategies should demonstrate a clear understanding of the heritage values of a building, site or area and its relationship with its surroundings. Through proactive management from the start of the development process, planners and developers should engage and collaborate with stakeholders so that the capital’s heritage contributes positively to its future. To ensure a full and detailed understanding of the local historic environment, stakeholders should include Historic England, London’s Parks and Gardens Trust, The Royal Parks, boroughs, heritage specialists, local communities and amenity societies.

7.1.6 Historically, London has demonstrated an ability to regenerate itself, which has added to the city’s distinctiveness and diversity of inter-connected places. Today urban renewal in London offers opportunities for the creative re-use of heritage assets and the historic environment as well as the enhancement, repair and beneficial re-use of heritage assets that are on the At Risk Register.[128] In some areas, this might be achieved by reflecting existing or original street patterns and blocks, or revealing and displaying archaeological remains; in others, it will be expressed by retaining and reusing buildings, spaces and features that play an important role in the local character of an area. Policy D1 London’s form, character and capacity for growth further addresses the issue of understanding character and context.

7.1.7 Heritage significance is defined as the archaeological, architectural, artistic or historic interest of a heritage asset. This may be represented in many ways, in an asset’s visual attributes, such as form, materials, architectural detail, design and setting, as well as through historic associations between people and a place, and where relevant, the historic relationships between heritage assets. Development that affects heritage assets and their settings should respond positively to the assets’ significance, local context and character to protect the contribution that settings make to the assets’ significance. In particular, consideration will need to be given to mitigating impacts from development that is not sympathetic in terms of scale, materials, details and form.

7.1.8 Where there is evidence of deliberate neglect of and/or damage to a heritage asset to help justify a development proposal, the deteriorated state of that asset will be disregarded when making a decision on a development proposal.

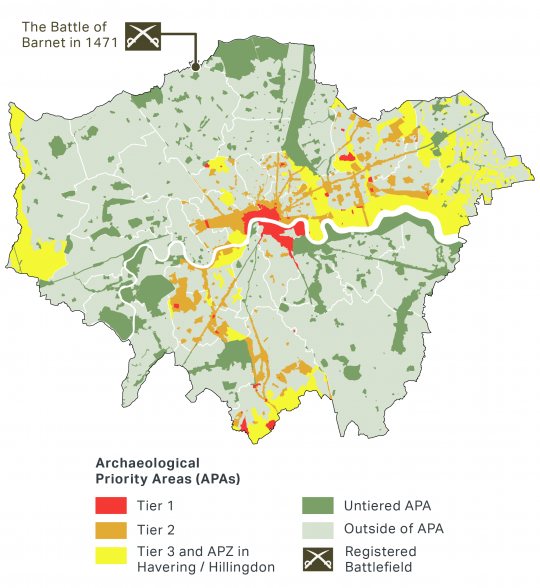

7.1.9 Understanding of London’s archaeology is continuously developing with much of it yet to be fully identified and interpreted. To help identify sites of archaeological interest, boroughs are expected to develop up-to-date Archaeological Priority Areas for plan-making and decision-taking. Up-to-date Archaeological Priority Areas (APAs) are classified using a tier system recognising their different degrees of archaeological significance and potential as presently understood. Tier 1 APAs help to identify where undesignated archaeological assets of equivalent significance to a scheduled monument – and which are subject to the same policies as designated assets – are known or likely to be present.

7.1.10 Across London, Local Plans identify areas that have known archaeological interest or potential. The whole of the City of London has high archaeological sensitivity whilst elsewhere the Greater London Archaeological Priority Area Review Programme is updating these areas using new consistent London-wide criteria (see Figure 7.4). Each new APA is assigned to a tier:

- Tier 1 is a defined area which is known, or strongly suspected, to contain a heritage asset of national significance, or which is otherwise of very high archaeological sensitivity.

- Tier 2 is a local area with specific evidence indicating the presence, or likely presence, of heritage assets of archaeological interest.

- Tier 3 is a landscape-scale zone within which there is evidence indicating the potential for heritage assets of archaeological interest to be discovered.

- Tier 4 (outside APA) covers any location that does not, on present evidence, merit inclusion within an Archaeological Priority Area.

- Other APAs which have not yet been reviewed are not assigned to a tier.

7.1.11 Developments will be expected to avoid or minimise harm to significant archaeological assets. In some cases, remains can be incorporated into and/or interpreted in new development. The physical assets should, where possible, be made available to the public on-site and opportunities taken to actively present the site’s archaeology. Where the archaeological asset cannot be preserved or managed on-site, appropriate provision must be made for the investigation, understanding, recording, dissemination and archiving of that asset, and must be undertaken by suitably-qualified individuals or organisations.

Figure 7.4 - Archaeological Priority Areas and Registered Battlefield

Policy HC2 World Heritage Sites

7.2.1 The UNESCO World Heritage Sites at Maritime Greenwich, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Palace of Westminster and Westminster Abbey including St Margaret’s Church, and the Tower of London are among the most important cultural heritage sites in the world and are a key feature of London’s identity as a world city. In ratifying the World Heritage Convention, the UK Government has made a commitment to protecting, conserving, presenting and transmitting to future generations the Outstanding Universal Value of World Heritage Sites and to protecting and conserving their settings. Much of this commitment is discharged by local authorities, including the GLA, through their effective implementation of national, regional, and local planning policies for conserving and enhancing the historic environment.

7.2.2 The context of each of the four London World Heritage Sites is markedly different and the qualities of each is conditioned by the character and form of its surroundings as well as other cultural, intellectual, spatial or functional relationships. The surrounding built environment must be carefully managed to ensure that the attributes of the World Heritage Sites that make them of Outstanding Universal Value are protected and enhanced, while allowing the surrounding area to change and evolve as it has for centuries.

7.2.3 The setting of London’s World Heritage Sites consists of the surroundings in which they are experienced, and is recognised as fundamentally contributing to the appreciation of a World Heritage Site’s Outstanding Universal Value. As all four of London’s World Heritage Sites are located along the River Thames, the setting of these sites includes the adjacent riverscape as well as the surrounding landscape. Changes to the setting can have an adverse, neutral or beneficial impact on the ability to appreciate the sites’ Outstanding Universal Value. The consideration of views is part of understanding potential impacts on the setting of the World Heritage Sites. Many views to and from World Heritage Sites are covered, in part, by the London Views Management Framework (see Policy HC3 Strategic and Local Views and Policy HC4 London View Management Framework). However, consideration of the attributes that contribute to their Outstanding Universal Value is likely to require other additional views to be considered. These should be set out in World Heritage Site Management Plans (see below), and supported wherever possible by the use of accurate 3D digital modelling and other best practice techniques.

7.2.4 Policies protecting the Outstanding Universal Value of World Heritage Sites (WHS) should be included in the Local Plans of those boroughs where visual impacts from developments could occur. It is expected that boroughs’ plans (including but not limited to the following) should contain such policies: City of London (Tower of London WHS); Royal Borough of Greenwich (Maritime Greenwich WHS); Hounslow (Royal Botanical Gardens Kew WHS); Lambeth (Westminster WHS); Lewisham (Maritime Greenwich WHS); Richmond (Royal Botanical Gardens Kew WHS); Southwark (Tower of London WHS, Westminster WHS); Tower Hamlets (Tower of London WHS, Maritime Greenwich WHS); Wandsworth (Westminster WHS); City of Westminster (Westminster WHS). Supplementary Planning Guidance will provide further guidance on settings and buffer zones.

7.2.5 Boroughs should ensure that their Local Plan policies support the management of World Heritage Sites, details of which can be found in World Heritage Site Management Plans. For Outstanding Universal Value, Management Plans should set out:

- the attributes that convey the Outstanding Universal Value, and

- the management systems to protect and enhance the Outstanding Universal Value of the World Heritage Sites.

7.2.6 The Mayor will support steering groups in managing the World Heritage Sites and will actively engage with stakeholders in the development and implementation of World Heritage Management Plans. It is expected that the boroughs with World Heritage Sites, GLA, Historic England and neighbouring boroughs will be part of the World Heritage Site Steering Groups that contribute to the management of the sites, including the drafting and adoption of Management Plans.

Policy HC3 Strategic and Local Views

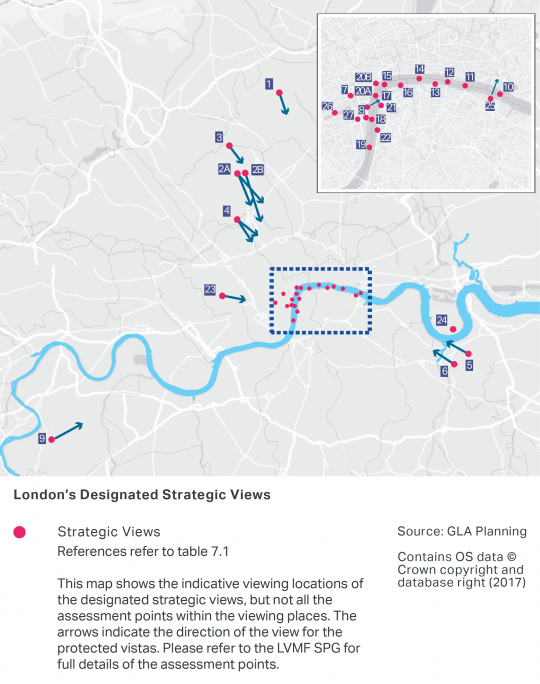

7.3.1 A number of views make a significant contribution to the image and character of London at the strategic level. This could be because of their composition, their contribution to the legibility of the city, or because they provide an opportunity to see key landmarks as part of a broader townscape, panorama or river prospect. The Mayor will seek to protect the composition and character of these views, particularly if they are subject to significant pressure from development. New development can make a positive contribution to the views and this should be encouraged, but where development is likely to compromise the setting or visibility of a key landmark it should be resisted. The views that the Mayor has designated are listed in Table 7.1, with Figure 7.5 showing the indicative viewing locations of these designated views.

7.3.2 There are three types of Strategic Views designated in the London Plan – London Panoramas, River Prospects, and Townscape Views (including Linear Views). Each view can be considered in three parts; the foreground, middle ground and background. The front and middle ground areas are the areas between the viewing place and/or the natural features that form its setting. The background area to a view extends away from the foreground or middle ground into the distance. Part of the background may include built or landscape elements that provide a backdrop to a Strategically-Important Landmark.

7.3.3 The Mayor identifies three Strategically-Important Landmarks in the designated views: St Paul’s Cathedral, the Palace of Westminster and the Tower of London. Within some views, a Protected Vista to a Strategically-Important Landmark will be defined and used to protect the viewer’s ability to recognise and appreciate the Strategically-Important Landmark. The Protected Vista is composed of two parts:

- Landmark Viewing Corridor – the area between the viewing place and a Strategically-Important Landmark that must be maintained if the landmark is to remain visible from the viewing place.

- Wider Setting Consultation Area – the area enclosing the Landmark Viewing Corridor in the foreground, middle ground and background of the Protected Vista. Development above a threshold height in this area could compromise the viewer’s ability to recognise and appreciate the Strategically-Important Landmark.

7.3.4 The London View Management Framework Supplementary Planning Guidance (LVMF SPG) provides further guidance on the management of views designated in this Plan. This includes plans for the management of views as seen from specific assessment points within the viewing places. The SPG provides advice on the management of the foreground, middle ground and background of each view. This guidance identifies viewing places within which viewing locations can be identified. It also specifies individual assessment points from which management guidance and assessment should be derived. Some views are experienced as a person moves through a viewing area and assessment of development proposals should consider this. The SPG provides guidance on the treatment of all parts of the view, and where appropriate the components of the Protected Vista for each view.

Table 7.1 - Designated Strategic Views

London Panoramas

Linear Views

River Prospects

Townscape Views

7.3.5 The Mayor will work with boroughs and landowners of the Protected Vista viewing locations to ensure the viewing points are clearly identified. Boroughs and landowners should manage the viewing locations to ensure they are accessible to the public and, where appropriate, mark the viewing location and provide information about landmarks that can be seen in the view. Vegetation in the foreground and middle ground of a view must be regularly maintained in accordance with the LVMF SPG management guidance to ensure the view is not obscured.

7.3.6 Clearly identifying local views in Local Plans and strategies enables the effective management of development in and around the views. This could take the form of geometrically defining the view requiring protection, in particular the assessment point and direction of the viewing location, through mapping or 3D modelling. Where local views are clearly identified they should be protected and managed in a similar manner as Strategic Views, following the principles of Policy HC4 London View Management Framework.

Figure 7.5 - Designated Strategic Views

Policy HC4 London View Management Framework

7.4.1 Protected Vistas are designed to preserve the viewer’s ability to recognise and appreciate a Strategically-Important Landmark from a designated viewing place. Development that exceeds the threshold plane of the Landmark Viewing Corridor will have a negative impact on the viewer’s ability to see the Strategically-Important Landmark and is therefore contrary to the London Plan. Development in the foreground, middle ground or background of a view can exceed the threshold plane of a Wider Setting Consultation Area if it does not damage the viewer’s ability to recognise and to appreciate the Strategically-Important Landmark and if it does not dominate the Strategically-Important Landmark in the foreground or middle ground of the view. Development in the background of a Protected Vista that is inside or outside of the Wider Setting Consultation area should not harm the composition of the Protected Vistas.

7.4.2 Development should make a positive contribution and where possible enhance the viewer’s ability to recognise Strategically-Important Landmarks. Where existing buildings currently detract from or block the view, this should not be used as justification for new development to likewise exceed the threshold height of the Landmark Viewing Corridor.

7.4.3 Opportunities to reinstate Landmark Viewing Corridors arising as a result of redevelopment and demolition of existing buildings that exceed Landmark Viewing Corridor threshold height should be taken whenever possible.

Policy HC5 Supporting London’s culture and creative industries

7.5.1 London’s rich cultural offer includes visual and performing arts, music, spectator sports, festivals and carnivals, pop-ups and street markets, and a diverse and innovative food scene, which is important for London’s cultural tourism. The vibrancy of London’s culture is integrally linked to the diverse communities of the city, and grassroots venues and community projects are as important as London’s famous cultural institutions in providing opportunities for all Londoners to experience and get involved in culture.

7.5.2 The capital’s cultural offer is often informed, supported and influenced by the work of the creative industries such as advertising, architecture, design, fashion, publishing, television, video games, radio and film. Cultural facilities and venues include premises for cultural production and consumption such as performing and visual arts studios, creative industries workspace, museums, theatres, cinemas, libraries, music, spectator sports, and other entertainment or performance venues, including pubs and night clubs. Although primarily serving other functions, the public realm, community facilities, places of worship, parks and skate-parks can provide important settings for a wide range of arts and cultural activities.

7.5.3 London’s culture sector and the creative industries deliver both economic and social benefits for the capital. In 2015, the Gross Value Added (GVA) of the creative industries in London was estimated at £42 billion, accounting for just under half of the UK total from these industries, and contributing 11.1 per cent to London’s total GVA. Cultural tourism supported 80,000 jobs and contributed £3.2 billion of GVA to London in 2013, just under a third of the overall contribution from the tourism sector as a whole. As well as being one of London’s most dynamic sectors, culture also plays a role in building strong communities, increasing healthy life outcomes and generating civic pride.

7.5.4 Despite this positive general picture, London’s competitive land market means that the industry is struggling to find sufficient venues to grow and thrive, and is losing essential spaces and venues for cultural production and consumption including pubs, night clubs, venues that host live or electronic music and rehearsal facilities. Creative businesses and artists also struggle to find workspace and secure long-term financing and business support as their activities are perceived to be ‘risky’ or of non-commercial value.

7.5.5 Boroughs are encouraged to develop an understanding of the existing cultural offer in their areas, evaluate what is unique or important to residents, workers and visitors and develop policies to protect those cultural assets and community spaces. Boroughs should draw on the Mayor’s forthcoming Cultural Infrastructure Plan to assess and develop their cultural offer. Boroughs should also consider how the cultural offer serves different groups of people (such as young people, BAME groups and the LGBT+ community), and where the cultural offer is lacking for particular groups. Boroughs should put in place policies and strategies to ensure that cultural facilities catering for such groups and communities are protected, especially facilities that are used in the evening and night time.

7.5.6 The loss of cultural venues, facilities or spaces can have a detrimental effect on an area, particularly when they serve a local community function. Where possible, boroughs should protect such cultural facilities and uses, and support alternative cultural uses, particularly those with an evening or night-time use, and consider nominations to designate them as Assets of Community Value. Where a development proposal leads to the loss of a venue or facility, boroughs should consider requiring the replacement of that facility or use.

7.5.7 Boroughs are encouraged to support opportunities to use vacant buildings and land for flexible and temporary meanwhile uses or ‘pop-ups’ especially for alternative cultural day and night-time uses. The use of temporary buildings and spaces for cultural and creative uses can help stimulate vibrancy, vitality and viability in town centres by creating social and economic value from vacant properties. Meanwhile uses can also help prevent blight in town centres and reduce the risk of arson, fly tipping and vandalism. The benefits of meanwhile use also include short-term affordable accommodation for SMEs and individuals, generating a short-term source of revenue for the local economy and providing new and interesting shops, cultural and other events and spaces, which can attract longer-term business investment. Parameters for any meanwhile use, particularly its longevity and associated obligations, should be established from the outset and agreed by all parties.

7.5.8 Events and activities such as festivals, seasonal markets, exhibitions, performances, outdoor concerts and busking are not always dependent on using a dedicated cultural facility or venue and can make use of a range of outdoor spaces including streets, parks and other public areas. These types of activities, which are often free, offer a way for everyone to experience and participate in London’s rich cultural life. The opportunity to incorporate these uses should be identified and facilitated through careful design and consideration of the impacts, for example on residents, visitors and biodiversity.

7.5.9 As well as protecting existing venues and facilities, boroughs should also work with a range of partners to develop and promote clusters of cultural activities and related uses and define them in their Local Plan. A successful Cultural Quarter should build on the existing cultural character of an area and encourage a mix of uses, including cafés, restaurants and bars alongside cultural assets and facilities, to attract visitors and generate interest. A Cultural Quarter can be used to form the basis for sustained cultural activity but may also include temporary activities and uses such as festivals, markets, exhibitions, performances and other cultural events.

7.5.10 Where appropriate, boroughs should use Cultural Quarters to seek synergies between cultural provision, schools, and higher and further education which can be used to nurture volunteering, new talent and audiences. This can include partnerships with a range of cultural organisations, such as libraries, museums, galleries, music venues, dance studios, and theatres.

7.5.11 Boroughs should maximise opportunities for developing Cultural Quarters in Opportunity Areas, other Areas for Regeneration and large-scale developments. The inclusion of new cultural venues and facilities can assist with place-making, creating an attractive and vibrant area for residents, workers and visitors, as well as helping to form the character and distinctiveness of a new place.

7.5.12 London is internationally-renowned for its historic environment and cultural institutions, which are major visitor attractions as well as making an enormous contribution to the capital’s culture and heritage. There are many areas in London which are rich in cultural heritage and have a unique cultural offer. These act as key visitor hubs for Londoners and domestic and international tourists and as such should be protected and promoted. They include: clusters of museums such as the South Kensington museums complex; the theatres, concert halls and galleries of the Southbank/Bankside/London Bridge area; the theatres and cinemas of the West End; Wembley Stadium and Wembley Arena; the Greenwich Riverside and O2 Centre; the Olympic Park; and London’s Arcadia including Kew Gardens, parks, historic buildings and landscapes between Hampton Court and Kew along the River Thames. Boroughs should identify these and other strategic clusters of cultural attractions in their Local Plans.

7.5.13 Creative industries play an important role in London’s economy and its cultural offer; and as a sector are growing at a faster rate than any other area of the economy. As part of his support for the creative industries, the Mayor is committed to working with boroughs and other relevant stakeholders to identify and set up Creative Enterprise Zones (CEZs). Setting up a CEZ can help boost the local economy of more deprived areas and support their regeneration. CEZs will support the provision of dedicated small industrial and creative workspaces and will seek to address issues of affordability and suitability of workspaces for artists and creative businesses.

7.5.14 CEZs should seek to protect, develop and deliver new spaces the creative industries need to produce, manufacture, design, rehearse and create cultural goods, as well as ancillary facilities where they can meet clients, network, share knowledge and showcase their work. Boroughs will be responsible for defining these areas in their Local Plans and developing policies to provide the workspace the industries need. This should include protecting existing workspace and encouraging new workspaces for the creative industries, ensuring that suitable business space and affordable workspace is made available in accordance with Policy E2 Providing suitable business space, Policy E3 Affordable workspace and Policy E8 Sector growth opportunities and clusters, and encouraging the temporary use of vacant buildings for creative uses. In developing policies and strategies for CEZs, Boroughs should engage with local CEZ consortiums, communities and businesses.

Policy HC6 Supporting the night-time economy

7.6.1 The night-time economy refers to all economic activity taking place between the hours of 6pm and 6am, and includes evening uses. Night-time economic activities include eating, drinking, entertainment, shopping and spectator sports, as well as hospitality, cleaning, wholesale and distribution, transport and medical services, which employ a large number of night-time workers.

7.6.2 The night-time economy is becoming increasingly important to London’s economy. The Mayor is keen to promote London as a 24-hour global city, taking advantage of London’s competitive edge and attractiveness for businesses and people looking to expand beyond the usual daytime economy into night-time economic opportunities. However, 24-hour activities are not suitable for every part of London, and boroughs should balance the needs of local residents in all parts of London with the economic benefits of promoting a night-time economy.

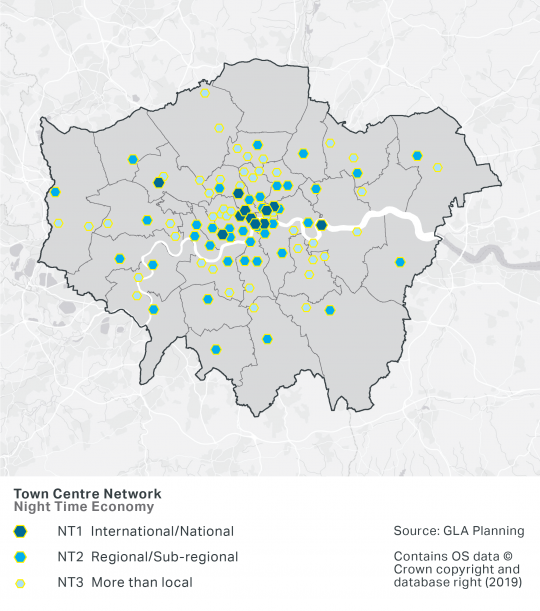

7.6.3 London’s night-time economy is generally focused in the Central Activities Zone (CAZ) and within town centres across the city. Different areas of night-time activity function at different scales and have different catchments. They have been classified, as set out in Table A1.1 and Figure 7.6, into three broad categories:

- NT1 – Areas of international or national significance

- NT2 – Areas of regional or sub-regional significance

- NT3 – Areas with more than local significance

7.6.4 Each night-time economy area will have its own character, which should be recognised and supported in order to maintain the rich diversity of London’s night-time economy. Areas of international or national significance play a crucial role in putting London on the world stage, bringing internationally-renowned culture, performers and productions. Regional and sub-regional areas attract visitors from across and beyond London, and often have one or more larger venues and a mature night-time economy. These are generally in London’s larger town centres. Areas with more than local significance draw visitors from other parts of London and tend to feature smaller venues and premises.

7.6.5 In addition, there are some town centres where the night-time economy serves the local area as well as other specific locations – such as London’s wholesale markets, major hospitals, and some industrial areas – where there is significant economic or service activity at night. This includes some retail and service industries, health services, policing and security, and transport and logistics. In exercising their various functions, boroughs should have regard to the strategic areas of night-time activity, as well as other night-time economic functions, and should set out strategies and policies that support the specific role of these areas in order to promote London’s night-time economy.

7.6.6 There are many benefits to promoting night-time economic activity such as generating jobs, improving income from leisure and tourism, providing opportunities for social interaction, and making town centres safer by increasing activity and passive surveillance. Managing issues such as transport, servicing, increased noise, crime, anti-social behaviour, perceptions of safety, the quality of the street environment, and the potential negative effects on the health and wellbeing of Londoners, will require specific approaches tailored to the night-time environment, activities and related behaviour. Boroughs are encouraged to consider appropriate management strategies and mitigation measures to reduce negative impacts on the quality of life of local residents, workers and night-time economy customers, particularly in areas with high concentrations of licensed premises. Boroughs should also take account of local circumstances when considering whether to concentrate or disperse evening and night-time activities in town centres or within the CAZ. Boroughs should consider applying for accreditation with schemes such as Purple Flag[130] which provide a standard of excellence in managing the night-time economy.

7.6.7 Large concentrations of night-time activities can result in some places lacking activity and vitality during the day. Boroughs should consider opportunities to encourage the daytime uses of buildings that are mainly used for night-time activities to help diversify the 24-hour offer. Similarly, boroughs should explore the benefits of expanding the range of night-time economy activities to include extending opening hours and alternative evening and night-time uses of existing daytime facilities such as shops, cafés, restaurants, markets, community centres, libraries, theatres and museums. The temporary use of spaces and venues in the evening and at night can enhance the vibrancy and vitality of the night-time economy, particularly meanwhile uses of vacant premises, for example as arts venues, nightclubs, bars or restaurants.

7.6.8 The recently introduced Night Tube that operates on many Tube lines throughout the weekend, and the extensive network of night buses, has helped to create a public transport system that can support a 24-hour city including making travel easier for London’s many night workers. Boroughs are encouraged to work with Transport for London (TfL) to take advantage of improved night-time public transport to identify areas where night-time economic activity can be promoted and enhanced in a safe and attractive way. This would include considering planning applications for night-time venues and activities to diversify and enhance the night-time offer in town centres, particularly those that are within or well-connected to Areas for Regeneration (see Policy SD10 Strategic and local regeneration). Outer London boroughs, in particular, should consider the opportunities offered by an extended Night Tube and Night Bus network to increase the night-time offer in town centres for local residents, workers and visitors.

7.6.9 Boroughs should explore the benefits of diversifying the night-time mix of uses, particularly in areas where there are high concentrations of licensed premises, along with extended opening times of public places and spaces. This can help attract a more diverse range of visitors, including those who feel excluded from alcohol-based entertainment activities. It can also help decrease crime, anti-social behaviour and the fear of crime.

7.6.10 The night-time economy doesn’t only happen inside; many night-time activities make use of outside spaces including the public realm, and enjoying the public spaces of the city at night is an important part of the night-time experience. This requires careful and co-ordinated management between a wide variety of stakeholders, including residents, to ensure that the city can be enjoyed at night to its fullest, and that the night-time economy complements rather than conflicts with daytime activities. Impacts such as noise and light pollution on local wildlife and biodiversity should be considered through appropriate location, design and scheduling, to address the requirements of Policy G6 Biodiversity and access to nature.

7.6.11 Making London’s night-time culture more enjoyable and inclusive requires ensuring a wide range of evening and night-time activities are on offer to London’s diverse population. In recent years, many valued night-time venues have been lost, and this has disproportionately affected particular groups. There are also groups of people who avoid town centres and night-time activities for a variety of reasons, for example physical barriers and lack of facilities for disabled people and older people, perceptions around safety and security particularly for women, those who feel excluded for socio-economic reasons and issues of staff attitudes towards, and awareness of, LGBT+ and BAME groups. Boroughs should work with land owners, investors and businesses to address perceived barriers to accessing the night-time economy and enhance the experience of London at night. This can include requiring new developments to provide accessible and gender-neutral toilets (see Policy S6 Public toilets), supporting venues that serve specific groups (for example through the LGBT+ Venues Charter),[131] working with local police and businesses to make streets and the public realm safer and more welcoming, ensuring cleansing services are procured to clean up litter and sanitise streets and public areas, and working with local businesses, local communities, TfL and logistics operators to optimise servicing that occurs at night or supports the night-time economy.

Figure 7.6 - Town centres and night-time economy roles – distinguishing those of international, sub-regional and more than local importance

Policy HC7 Protecting public houses

7.7.1 Pubs are a unique and intrinsic part of British culture. Many pubs are steeped in history and are part of London’s built, social and cultural heritage. Whether alone, or as part of a cultural mix of activities or venues, pubs are often an integral part of an area’s day, evening and night-time culture and economy. An individual pub can also be at the heart of a community’s social life, often providing a local meeting place, a venue for entertainment or a focus for social gatherings. More recently, some pubs have started providing library services and parcel collection points as well as food to increase their offer and appeal to a wider clientele.

7.7.2 Through their unique and varied roles, pubs can contribute to the regeneration of town centres, Cultural Quarters and local tourism, as well as providing a focus for existing and new communities, and meeting the needs of particular groups, such as the LGBT+ and BAME communities. However, pubs are under threat from closure and redevelopment pressures, with nearly 1,200 pubs in London lost in 15 years.[132] The recent changes to the Town and Country Planning Act (General Permitted Development Order) (England) (2015) have, however, removed permitted development rights that previously allowed pubs and bars to change planning Use Class to shops, financial and professional services, restaurants and cafés without prior planning approval. This change in legislation offers greater protection for pubs and also incorporates a permitted development right that allows pub owners to introduce a new mixed use (A3/A4) which should provide flexibility to enhance a food offer beyond what was previously allowed as ancillary to the main pub use.

7.7.3 Many pubs are popular because they have intrinsic character. This is often derived from their architecture, interior and exterior fittings, their long-standing use as a public house, their history, especially as a place of socialising and entertainment catering for particular groups, their ties to local sports and other societies, or simply their role as a meeting place for the local community. In developing strategies and policies to enhance and retain pubs, boroughs should consider the individual character of pubs in their area and the broad range of characteristics, functions and activities that give pubs their particular value, including opportunities for flexible working.

7.7.4 New pubs, especially as part of a redevelopment or regeneration scheme, can provide a cultural and social focus for a neighbourhood, particularly where they offer a diverse range of services, community functions and job opportunities. However, it is important when considering proposals for new pubs that boroughs take account of issues such as cumulative impact zones, the Agent of Change principle (see Policy D13 Agent of Change) and any potential negative impacts. Boroughs should consider the replacement of existing pubs in redevelopment and regeneration schemes, where the loss of an existing pub is considered acceptable.

7.7.5 Boroughs should take a positive approach to designating pubs as an Asset of Community Value (ACV) when nominated by a community group. Listing a pub as an ACV gives voluntary groups and organisations the opportunity to bid for it if it is put up for sale. The ‘right to bid’ is not a right to buy and although owners of the asset have to consider bids from community groups, they do not have to accept them. An ACV listing does, nevertheless, give communities an increased chance to save a valued pub or other local facility. Boroughs should consider the listing of a pub as an ACV as a material consideration when assessing applications for a change of use and consider compulsory purchase orders where appropriate.

7.7.6 When assessing whether a pub has heritage, cultural, economic or social value, boroughs should take into consideration a broad range of characteristics, including whether the pub:

a. is in a Conservation Area

b.is a locally- or statutorily-listed building

c. has a licence for entertainment, events, film, performances, music or sport

d. operates or is closely associated with a sports club or team

e. has rooms or areas for hire

f. is making a positive contribution to the night-time economy

g. is making a positive contribution to the local community

h. is catering for one or more specific group or community.

7.7.7 To demonstrate authoritative marketing evidence that there is no realistic prospect of a building being used as a pub in the foreseeable future, boroughs should require proof that all reasonable measures have been taken to market the pub to other potential operators. The pub should have been marketed as a pub for at least 24 months at an agreed price following an independent valuation, and in a condition that allows the property to continue functioning as a pub. The business should have been offered for sale locally and London-wide in appropriate publications and through relevant specialised agents.

7.7.8 Many pubs built on more than one floor include ancillary uses such as function rooms and staff accommodation. Potential profit from development makes the conversion of upper pub floors to residential use extremely attractive to owners. Beer gardens and other outside space are also at risk of loss to residential development. The change to residential use of these areas can limit the operational flexibility of the pub, make it less attractive to customers, and prevent ancillary spaces being used by the local community. It can also threaten the viability of a pub through increased complaints about noise and other issues from new residents. Boroughs should resist proposals for redevelopment of associated accommodation, facilities or development within the curtilage of the public house that would compromise the operation or viability of a public house. Where such proposals would not compromise the operation or viability of the public house, developers must put in place measures that would mitigate the impacts of noise for new and subsequent residents (see Policy D13 Agent of Change).

[127] The GLHER is a public record managed by Historic England and can be accessed by visiting the GLHER office and through remote searches that involve the supply of digital GLHER data. More information can be found at: https://historicengland.org.uk/services-skills/our-planning-services/greater-london-archaeology-advisory-service/

[128] The Heritage at Risk Register is produced annually as part of Historic England’s Heritage at Risk programme. The Register includes buildings or structures, places of worship, archaeological sites, battlefields, wrecks, parks and gardens, and conservation area known to be at risk as a result of neglect, decay or inappropriate development. Further information can be found at: https://historicengland.org.uk/advice/heritage-at-risk/

[131] https://www.london.gov.uk/what-we-do/arts-and-culture/how-were-protecting-lgbt-nightlife-venues

[132] Closing time: London’s public houses, GLA Economics, April 2017