Key information

Publication type: General

Publication date:

Contents

1. Introduction

New Updates - August 2023

Tender has worked in partnership with the Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime (MOPAC), teachers, youth workers and partner organisations, to develop the activities and resources within this toolkit to effectively engage young people on the issues of gender-based abuse, including relationship abuse and sexual violence.

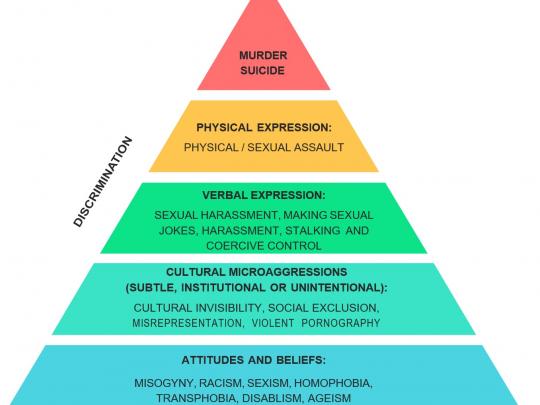

With rising levels of gender-based abuse in the country in recent yearsReference:1, research has proven that if pervasive misogynistic attitudes towards women and girls are left unchecked, they can allow harmful and violent behaviours, both online and ‘in real life’, to increase in volume and visibility and to escalate. Even seemingly ‘harmless’ attitudes and behaviour can lead to intimidation, threats, and violence.

Violent behaviour does not erupt out of nowhere and the pyramid diagram below demonstrates how attitudes and beliefs will develop into micro-aggressions, which, if unchallenged or unchecked will form into verbal and physical behaviours that are intended to humiliate, threaten and harm. It is imperative therefore that education around attitudes and beliefs is provided in order to prevent harmful behaviours from escalating. This toolkit will enable professionals to educate children and young people, about gender-based abuse, creating a shift in attitudes, behaviour and knowledge, and supporting them to challenge any tolerance of gender-based violence and abuse.

The toolkit is essentially made up of two key elements. One contains detailed information to support educational professionals in understanding gender-based abuse, with context information and statistics to enable discussions with young people. The second element contains activities to begin conversations with young people about gender-based abuse as well as activities and discussion points that can be adapted to respond to the needs of the group or a specific theme/topic you may wish to discuss. With Tender’s knowledge of the National Curriculum and statutory requirements around PSHE, these activities will support the delivery of Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) as well.

As the statistics in this toolkit will demonstrate, gender-based abuse is prevalent in society. It is therefore possible that professionals using this toolkit may have experienced or witnessed gender-based abuse and the material discussed may create uncomfortable or upsetting feelings. We acknowledge that this can be a difficult subject and would encourage the reader to take care and seek support if necessary. We have provided general information in the Support activity about services and organisations that may be of help and support to anyone in this situation.

We welcome feedback and sharing ideas of how this toolkit has been used and adapted by those who use it.

About Tender

Tender is an arts-educational charity committed to preventing domestic abuse and sexual violence in the lives of children and young people by promoting healthy relationships. Founded in 2003, we work with schools, youth settings and communities to tackle attitudes which enable and condone inequality and violence, while providing a safe, fun space for children and young people to explore their expectations of relationships.

Tender aims to:

- Educate children and young people about healthy and unhealthy relationships.

- Challenge attitudes which tolerate, condone and conceal abusive relationships.

- Empower children and young people to speak up and seek support if they or a friend is experiencing abuse.

2. Have A Word Campaign Video

Playing this video will set cookies from YouTube/Google

3. Young people and gender-based abuse

Gender-based Violence and Abuse definition

“The definition of discrimination includes gender-based violence, that is, [abuse and] violence that is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately. It includes acts that inflict physical, mental or sexual harm or suffering, threats of such acts, coercion and other deprivations of liberty.”Reference:2

It can include but isn’t limited to:

- domestic abuse

- sexual violence and rape

- stalking and harassment

- trafficking of women

- female genital mutilation (often referred to as FGM)

- intimidation and harassment at work, in education or in public

- forced prostitution

- forced marriage

- ‘honour’ crimes

There is evidence that young people (16-24 years old) are at the highest risk of experiencing domestic abuseReference:3, one of the most common forms of gender-based abuse.

Crime Survey of England and Wales data, as reported by the Office for National Statistics, showed that in the year ending March 2022 the victim was female in 74.1% of domestic abuse-related crimesReference:4. According to an NSPCC study exploring abuse in teenage intimate relationshipsReference:5, 11% of girls reported severe physical violence from a partner compared to only 4% of boys who reported similar cases of physical violence. On one hand, it shows the extreme ‘gender asymmetry’ in the issue. On another, it could also mean that boys who experience such abuse are ‘less visible’ to the services: a Home Office bulletin in 2008 noted that women were more likely to tell someone about partner abuse than menReference:6, a finding supported by crime statistics for the year up to March 2018, which showed that 50.8% reported telling anyone about abuse, compared to 81.3% of female victimsReference:7.

It is important that children and young people know about healthy and unhealthy relationships and how to get support. We know that by challenging problematic behaviour, language, beliefs and attitudes we can contribute to ending a culture of abuse that is disproportionately against women and girls.

This toolkit was created with the objective of engaging young people on the issues of gender-based abuse, focusing primarily focuses on the issues facing 16-24 year-olds. Additionally, keeping in mind that the gender-based violence is faced disproportionately by girls and young womenReference:8, VAWG (Violence Against Women and Girls) literature has informed much of the content in this toolkit. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that domestic abuse does not discriminate, and is experienced by all genders, albeit in different ways and to different extents.

Key statistics about relationship abuse and young people:

- The 2014 Girls’ Attitudes Survey conducted by the Girl Guides of 1,405 girls and young women showed that 59% of girls aged 7-21 have reported some form of sexual harassment at school or collegeReference:9.

- A school-based survey of 1,000 14 – 15 year-olds in England showed that 41% of girls and 14% of boys in an intimate relationship had experienced some form of sexual violence from their partnerReference:10.

- A third of all sexual abuse that children experience is committed by other childrenReference:11.

Key statistics about the extent of relationship abuse in the UK:

-

In 2021-22, nearly 2.4 million people aged 16-74 years in England and Wales suffered some form of domestic abuse: 1.7 million female victim-survivors and 699,000 male victim-survivorsReference:12.

-

Almost 30% of women will experience some form of domestic abuse after the age of 16Reference:13.

-

Two women a week are killed by a current or former partner in England and Wales aloneReference:14.

-

Black women were 14% less likely to be referred to Refuge for support by Police than white survivors of domestic abuse between March 2020 – June 2021Reference:15.

-

One 2017 study by SafeLives found that disabled women are twice as likely to experience domestic abuse as non-disabled womenReference:16. The study involved 925 disabled and 5153 non-disabled victims. According to ONS dataReference:17, adults with a disability were more likely to be victims of any domestic abuse than those with a disability (10.3% and 4% respectively).

-

Further, the same SafeLives study found that disabled people who are experiencing domestic abuse are twice as likely to have previously planned or attempted suicide (22% vs 11%)Reference:18.

-

In research conducted by Galop in 2018 of their domestic abuse advisory service, over four-fifths of lesbian women disclosed abuse from a female perpetrator (based on a sample of 626 unique LGBT+ victim-survivors)Reference:19.

-

The Galop research also found LGBT+ victims/survivors are almost twice as likely to suffer abuse by multiple perpetrators compared to non-LGBT+ victims/survivorsReference:20.

-

A 2021 Interventions Alliance report cites a 2005 study which reports that a woman facing domestic abuse has to make 11 contacts with agencies before getting the help she needs. However, this rises to 17 if she is Black, Asian or Minority EthnicReference:21.

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is a theoretical framework for understanding power and oppression through the socio-historical and political struggles of Black resistance and liberation movements, originally developed through critical, Black, feminist activismReference:23.

Kimberlé CrenshawReference:23 identified that a person’s interactions with the world are not just solely based on one aspect of their identity but are layered and multifaceted; interactions in which racism, sexism, ableism, classism and homophobia are experienced simultaneously.

For example, Rebecca is Black and Ethiopian. She is 14 years old, from a working-class background and her family follows Islam. A boy at school has started making sexual remarks about her body, sitting close to her on the school bus and recently he pushed himself against her as they passed in the school corridor. When looking through an intersectional lens Rebecca may experience multiple forms of oppression at once, such as racism, sexism, ageism, classism and religious discrimination. Her experience and views of professionals and services may be influenced by the combined oppressions and social inequalities she has experienced and create barriers to her speaking to a teacher about being sexually assaulted and harassed at school.

The adultification of Black girls is also an issue that professionals working with young people need to be aware of. Tender have worked with Listen UpReference:24, an organisation working to embed intersectionality & systemic thinking in child protection practice, policy & research. Founder of Listen Up, Jahnine Davis, summarised our responsibilities as professionals in 2022:

“If we are viewing some groups of children as being deviant and when we look at it through that intersectional lens, for example Black girls being more likely to be seen as “hyper sexualised”, the “jezebel”, and Black boys more likely to be seen as “aggressive”, and “angry”, ultimately the impact means there is a dereliction of our safeguarding duty…. Adultification can lead to professionals placing a level of responsibilisation on Black children to protect themselves instead of their responsibility to safeguard and protect them.”Reference:25

Whilst domestic abuse can impact the lives of women of all backgrounds, our society does not treat all victims of abuse equally. We encourage you to remain informed and aware of the various combined oppressions victim-survivors may encounter. In particular, those from minoritised and marginalised backgrounds, where racism and other forms of discrimination are likely to impact how some victim-survivors are seen or unseen. As professionals, we must remain empathetic to combined oppressions and identify as well as challenge our own

4. What is domestic abuse?

It is useful to note that when working with 11- 18 year olds, it’s beneficial to use the term ‘relationship abuse’ or ‘unhealthy relationship’ rather than ‘domestic abuse’. Young people often disengage when hearing the term ‘domestic abuse’, as they immediately assume it is referring to abuse between adults within the context of a home; re-establishing the subject as healthy and unhealthy relationships enables young people to view it as an immediate and relevant issue to their circumstances.

However, as this toolkit is directed at professionals, we will generally use legal terms such as ‘domestic abuse’ and ‘sexual violence’ as this is how the subject is widely used in statutory documents and guidance.

The following alternatives are often used interchangeably with the term ‘domestic abuse’:

- Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)

- Dating Violence

- Domestic Violence

- Gender-based Violence or Gender-based Abuse

- Gender Violence/Abuse

Young people often attribute the word “violence” to mean physical harm, so we would also encourage the use of the word “abuse”.

Domestic Abuse definition

“Any incident or pattern of incidents of controlling, coercive or threatening behaviour, violence or abuse between those aged 16 or over who are, or have been, intimate partners or family members, regardless of gender or sexuality.”Reference:26.

This can encompass but is not limited to the following types of abuse:

Psychological and Emotional:

Regular and deliberate use of a range of words and non-physical actions used with the purpose to manipulate, hurt, weaken or frighten a person mentally and emotionally; and/ or distort, confuse or influence a person’s thoughts and actions within their everyday lives, changing their sense of self and harming their wellbeingReference:27

Physical:

Any form of physical harm such as hitting, throwing, poisoning, burning or scalding, drowning, restraining, non-fatal strangulation and ultimately death.

Sexual:

Forcing or enticing the victim-survivor to take part in sexual activities, which may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing. It may also include non- contact activities, such as being forced to watch sexual activities or take and send sexual images.

Financial or Economic:

control over the other partner’s access to economic resources, which diminishes the victim-survivor’s capacity to support themselves and forces them to depend on the perpetrator financially.

Online:

This type of abuse is not part of the legal definition of domestic abuse, but Tender includes this when working with children, young people and adults to explore mobile phone and online technologies that can be used to harm others.

Domestic abuse also includes coercive control:

Coercive control is an act or a pattern of acts of assault, threats, humiliation and intimidation or other abuse that is used to harm, punish, or frighten their victim- survivors. This controlling behaviour is designed to make a person dependent by isolating them from support, exploiting them, depriving them of independence and regulating their everyday behaviour. Coercive control creates invisible chains and a sense of fear that pervades all elements of a victim-survivor’s life. It works to limit their human rights by depriving them of their liberty and reducing their ability for actionReference:28. The Domestic Abuse Act 2021 has extended the controlling or coercive behaviour offence to cover post-separation abuse.

Who experiences domestic abuse?

As evidenced within this toolkit, domestic abuse and sexual violence is a gendered issue. According to the most recent dataReference:29, nearly 30% of women have experienced some form of domestic abuse since the age of 16, compared to 14% of men. This means gender neutrality is inaccurate and unhelpful to women and men experiencing abuse or violence. It does not acknowledge the differences in experience of abuse between male and female victim-survivors or the differences in responses by services required to support victim-survivors of different genders to leave an abusive relationship.

Much of what is in this toolkit, including equality, respect, healthy relationships, responsibility and choice, applies to other circumstances, including heterosexual and LGBT+ intimate relationships and relationships with family and friends. When working with young people, it is helpful to present unbiased facts about gender-based abuse, when possible, to allow young people to draw their conclusions and apply them to their situations.

As discussed previously, we encourage you to look at domestic abuse through an intersectional lens and recognise the additional barriers facing victim-survivors from minoritised and marginalised backgrounds, and those who have experienced other types of crime such as human trafficking. These victim-survivors are likely to have experienced racism, ableism, sexism, ageism, classism, homophobia and other forms of discrimination simultaneously.

Our stance needs to be very clear: relationship abuse is always a choice made by the perpetrator and it is never acceptable, whatever the gender or sexuality of the perpetrator.

It is also important to understand that everyone is at risk, so they can get help if they recognise early warning signs in their relationship and offer support if someone they know is experiencing abuse. If someone believes it can only happen to specific people, they might miss the warning signs if someone experiencing abuse doesn’t fit with their perception of a victim-survivor.

5. Sexual violence and harassment

Sexual violence and sexual harassment can occur between two children or young people of any age and gender. It can also occur through a group of children or young people sexually assaulting or sexually harassing a single child/ young person or group of children/young people. Children and young people who are victim-survivors of sexual violence and sexual harassment will likely find the experience stressful and distressing. This will, in all likelihood, adversely affect their educational attainment.

Sexual violence and sexual harassment exist on a continuum and may overlap; they can occur online and offline (both physical and verbal) and are never acceptable. It is important that all victim-survivors are taken seriously and offered support. Professionals should be aware that some groups are potentially more at risk, as evidence shows girls, children with Special Educational Needs and Disability (SEND) and LGBT+ children are at greater risk. Professionals should be aware of the importance of:

- making clear that sexual violence and sexual harassment is not acceptable, will never be tolerated and is not an inevitable part of growing up.

- not tolerating or dismissing sexual violence or sexual harassment as “banter”, “part of growing up”, “just having a laugh” or “boys being boys.”

- challenging behaviours (potentially criminal in nature), such as grabbing bottoms, breasts and genitalia, flicking bras and lifting up skirts. Dismissing or tolerating such behaviours risks normalising them.

What is sexual violence?

Whilst it is often not useful or productive to discuss the law in detail with young people, because it can distract from key learning points, it is useful for professionals to be aware of legislation as a referral point in discussion. When referring to sexual violence we are referring to sexual violence offences under the Sexual Offences Act 2003 as described below:

Rape:

A person (A) commits an offence of rape if: they intentionally penetrate the vagina, anus or mouth of another person (B) with their penis, B does not consent to the penetration and A does not reasonably believe that B consents. ‘Stealthing’ is when a sexual partner removes a condom during sex non- consensually and is considered rape by UK law.

Assault by Penetration:

A person (A) commits an offence if: s/he intentionally penetrates the vagina or anus of another person (B) with a part of her/his body or anything else, the penetration is sexual, B does not consent to the penetration and A does not reasonably believe that B consents.

Sexual Assault:

A person (A) commits an offence of sexual assault if: s/he intentionally touches another person (B), the touching is sexual, B does not consent to the touching and A does not reasonably believe that B consents.

If young people ask: "Can a woman rape a man?"

In the eyes of the law, only someone who has a penis can commit the act of rape, so the answer is no. However, there is an additional offence of ‘assault by penetration’ which covers non-consensual penetration by other body parts or objects. Both men and women can be charged with this offence, which carries the same sentencing guidelines as rape, with a maximum life term of imprisonment.

Rape myths

What is consent?

There are many myths about rape and other forms of sexual violence in our society which can reinforce feelings of shame, guilt and self-blame for the women and girls who have experienced sexual assault. These also form barriers to victim-survivors getting support. We often hear rape stereotypes and myths in our workshops with young people, such as:

Myth: People lie about being raped or sexual abuse because they regretted doing it, have been rejected by the person they’re accusing or just want attention.

See ‘Common Challenging Statements’ sections for more information and statistics. You may be able to think of more myths you could discuss with young people, or they may suggest themselves. Rape CrisisReference:32 has created a useful guide to rape myths vs facts, including how to respond to them.

The Sexual Offences Act 2003 says that someone consents to sexual activity if they:

- Agree by choice and

- Have both the freedom and capacity to make that choice.

Consent to sexual activity may be given to one sort of sexual activity but not another, e.g.to vaginal but not anal sex or penetration with conditions, such as wearing a condom. Consent can be withdrawn at any time during sexual activity and each time activity occurs. Someone consents to vaginal, anal or oral penetration only if they agree by choice to that penetration and have the freedom and capacity to make that choice. The age of consent in the UK is 16 years old. This is the age when young people can legally take part in sexual activity regardless of their sex or gender. Although children over the age of 16 can legally consent to sexual activity, the law gives extra protection to anyone who is under 18 years old as they may still be vulnerable to harm through an abusive sexual relationship.

It is illegal:

- to take, show or distribute indecent photographs of a child under the age of 18 (this includes images shared through sexting or sharing nudes)

- to sexually exploit a child under the age of 18 for a person in a position of trust (for example teachers or care workers)

- to engage in sexual activity with anyone under the age of 18 who is in the care of their organisation.

Consent can be a difficult issue to discuss with young people, but it is essential, nonetheless. Rape and sexual assault can occur without the victim-survivor saying ‘no’ – there are other reasons why they may be unable to give consent: they may be incapacitated by alcohol or drugs, or they may feel intimidated or pressured to say ‘yes’. Everybody has the right to change their mind about giving consent at any time. Giving consent once does not assume consent every time.

Sexual harassment and bullying

When referring to sexual harassment and bullying we mean ‘unwanted conduct of a sexual nature’ that can occur online and offline, and when sexuality or gender is used as a weapon. Sexual harassment and bullying are likely to: violate a student’s dignity, and/or make them feel intimidated, degraded or humiliated and/ or create a hostile, offensive or sexualised environment.

Whilst not intended to be an exhaustive list, sexual harassment and bullying can include:

- sexual comments, such as: telling sexual stories, making lewd comments, making sexual remarks about clothes and appearance and calling someone sexualised names.

- sexual “jokes” or taunting.

- stalking someone.

- physical behaviour, such as: deliberately brushing against someone, interfering with someone’s clothes (schools and colleges should be considering when any of this crosses a line into sexual violence - it is important to talk to and consider the experience of the victim-survivor) and displaying pictures, photos or drawings of a sexual nature.

- online sexual harassment. This may be standalone, or part of a wider pattern of sexual harassment and/or sexual violence. It may include:

- non-consensual sharing of sexual images and videos.

- sexualised online bullying.

- unwanted sexual comments and messages, including, on social media.

- sexual exploitation; coercion and threats.

- upskirting - typically involves someone taking a picture under another person’s clothing without their knowledge, with the intention of viewing their genitals or buttocks (with or without underwear).

Incidence of sexual harassment and bullying in schools in the UKReference:33

- 45% of teenage girls have had their bottom or breasts groped against their willReference:34.

- 38% of young people have received unwanted sexual imagesReference:35.

- 37% hear ‘slag’ used often or all the timeReference:36.

- Stonewall’s School report of 2017 based on 3,713 responses to an online questionnaire found that 45% of LGBT pupils, including 64% of trans pupils have experienced homophobic bullying in schoolReference:37.

- 64% of teachers in mixed-sex secondary schools hear sexist language in school on at least a weekly basis. 29% report that sexist language is a daily occurrence (based on a survey of 1,634 teachers in England and Wales)Reference:38.

- Stonewall’s School report of 2017 based on 3,713 responses to an online questionnaire found that 45% of LGBT pupil who are bullied for being LGBT never tell anyone about the bullyingReference:39.

The data from the National Union of Teachers Policy Statement published in 2007 is no longer accessible online. Please note these figures may be outdated, and should be used as indicative of these issues rather than reflecting current national statistics.

These statistics reveal the necessity of tackling sexual harassment and bullying among children and young people at an early stage. Every child or young person has the right to be happy and safe in school and at home. It is vital that children and young people have as broad an understanding of the issue as possible in order to recognise early warning signs of harassment and bullying and to avoid potentially difficult situations (especially around sexting).

Sexual Bullying/ Gender-Based Bullying

Sexual bullying – sometimes referred to as “gender-based bullying” - is defined as “any bullying behaviour, whether physical or non- physical, that is based on, or “weaponises”, a person’s sexuality or gender (perceived or actual) against them. This is most commonly directed at girls, young people who identify as LGBTQ+ and children/young people who are perceived to be acting outside of “acceptable” gender norms. It can be carried out to a person’s face, behind their back or via technology.” Sexual bullying can take the form of any of the following behaviours:

- Teasing, excluding or putting someone down by referring to:

- their gender and/or negative gender stereotypes (e.g. girls are stupid, boys don’t cry)

- their sexual activity or lack of activity (perceived or actual)

- their sexual orientation (perceived or actual)

- their body/developing body (e.g. the size of their breasts, bottom or muscles)

- Excluding or isolating peers due to their gender, or for acting outside of perceived “gender norms” (This can and often does include transphobic or homophobic language, e.g. “that’s so gay”).

- Not respecting personal boundaries or touching parts of their body without consent.

- Putting pressure on someone to act in a sexualised way.

- Sending/sharing of sexual or explicit images without consent, and/or coercing someone to do so.

- Using sexual words to put someone down (e.g. calling someone ‘slut’, ‘sket’ or ‘bitch’).

- Making threats or jokes about serious and frightening subjects like rape

- Spreading rumours about someone’s sexuality and sex life (including graffiti, texts and social media).

Incidence of Sexual Abuse and Harassment

- 64% girls aged 13-21 experienced sexual harassment in 2017Reference:40.

- Ofsted’s 2021 review of sexual abuse in schools and colleges found that 79% of girls and 38% boys think sexual assault happens 'a lot' or 'sometimes' amongst people their ageReference:41.

- The review found that 92% of girls, and 74% of boys, said sexist name-calling happens a lot or sometimes to them or their friendsReference:42.

- Furthermore, 90% of girls, and nearly 50% of boys, said being sent explicit pictures or videos of things they did not want to see happens a lot or sometimes to them or their peersReference:43.

- Stonewall’s School report of 2017 based on 3,713 responses to an online questionnaire found nearly half of lesbian, gay, bi and trans pupils (45%) – including 64% of trans pupils – are bullied for being lesbian, gay, bisexual or transsexual at school. This same report found that 40% of pupils who have experienced homophobic bullying have skipped school because of itReference:44.

Impact of sexual bullying

- Sexual bullying can lead to mental/physical health problems, low self-esteem, substance abuse, lower participation in the classroom, loss of concentration and lower academic achievementReference:45.

- Tolerance of these incidents can lead to more sexual bullying, and potentially worse behavioursReference:46.

- In 2006-7, 3,500 students were suspended for sexual bullying, 1/3 of which were from primary schoolsReference:47.

Sharing explicit images

For anyone under the age of 18, sending a naked image of themselves via text message or social media is illegal. It counts as an offence of distributing an indecent image of a child and is something they could receive a police caution. They could even be listed on the sex offenders register. The law doesn’t distinguish between an indecent image of a young person’s own body and an indecent image of someone else. Even though the age of sexual consent is 16, the age for distributing indecent images is 18. That means that a 17-year-old who can legally have sex cannot legally send a naked image.

As detailed below in ‘Child sexual exploitation’, a young person could also be pressured and coerced into creating and sending an explicit image. There are other laws that cover the sending of indecent images, for example, if someone sends a naked image of themselves to someone who is likely to be upset by it, that could be a crime under the Malicious Communications Act 2003.

Image-based sexual abuse

Image-based sexual abuse - also referred to as ‘revenge porn’ - is not simply about revenge; it is about power, control and humiliationReference:48. Image-based sexual abuse is the sharing of private, sexual materials, either photos or videos, of another person without their consent and with the purpose of causing embarrassment, distress or harm. The offence applies online and offline, for example sharing by text and email or showing someone a physical or electronic image. This offence, was previously prosecuted using a range of existing laws, such as the Communications Act 2003 and the Malicious Communications Act 1988.

However, as of 2015, there is a specific offence for this practice and those found guilty of the crime could face a sentence of up to two years in prison. The new offence criminalises sharing private, sexual photographs or films, where what is shown would not usually be seen in public. Sexual material not only covers images that show the genitals but also anything that a reasonable person would consider to be sexual, so this could be a picture of someone who is engaged in sexual behaviour or posing in a sexually provocative way.

The “right to be forgotten” can protect victim- survivors of image-based sexual abuse, and in 2015 Google took a stance against image-based sexual abuse, saying it honours requests to remove intimate images and videos shared without the consent of subjects from its search results.

Child sexual exploitation

This is a form of child sexual abuse and is when an individual or group coerces, manipulates and/ or deceives a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the child needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator/s. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact, it can also occur through the use of technology, or a combination of both. It often starts with online or offline ‘grooming’ as defined by the NSPCC: Grooming is when someone builds a relationship, trust and emotional connection with a child or young person so they can manipulate, exploit and abuse them. Children and young people who are groomed can be sexually abused, exploited or traffickedReference:49.

Like all forms of child sex abuse, child sexual exploitation:

- can affect any child or young person (male or female) under the age of 18 years, including 16- and 17-year olds who can legally consent to have sex.

- is still abuse even if the sexual activity appears consensual (remember a child cannot give consent to their abuse).

- can include both contact (penetrative and non-penetrative acts) and noncontact sexual activity.

- can involve force and/or enticement-based methods of compliance and may, or may not, be accompanied by abuse or threats of abuse.

- may occur without the child or young person’s immediate knowledge (e.g. through others copying videos or images they have created and posted on social media).

- can be perpetrated by individuals or groups, males or females, and children or adults.

The abuse can be a one-off occurrence or a series of incidents over time and range from opportunistic to complex organised abuse and is typified by some form of power imbalance in favour of those perpetrating the abuse. Whilst age may be the most obvious, this power imbalance can also be due to other factors, including gender, sexual identity, cognitive ability, physical strength, status, and access to economic or other resources.

Some of the following signs may be indicators of child sexual exploitation:

- children who appear with unexplained gifts or new possessions.

- children who associate with other young people involved in exploitation.

- children who have older boyfriends or girlfriends.

- children who suffer from sexually transmitted infections or become pregnant.

- children who suffer from changes in emotional wellbeing.

- children who misuse drugs and alcohol.

- children who go missing for periods of time or regularly come home late.

- children who regularly miss school or education or do not take part in educationReference:50.

6. Stalking

Stalking is persistent and unwanted attention that makes someone feel pestered, harassed and living in a state of fear and anxiety. It includes behaviour that happens two or more times, directed at or towards someone by another person; this could be a partner, ex-partner, friend, family member, colleague or stranger. It’s important not to dismiss these behaviours if the victim knows the person because it is still stalking and is still an offence. Cyberstalking is when a perpetrator repeatedly monitors and harasses someone using computers or mobile phones via the internet, email, instant messaging, text messaging, or over social networking sites.

The Protection of Freedoms Act 2012Reference:51 includes a list of possible behaviours but isn’t exhaustive:

- regularly following a person

- contacting, or attempting to contact, a person by any means

- repeatedly turning up where someone lives, goes to school or regularly visits

- identity theft (signing-up to services, buying things in someone’s name)

- publishing any statement or other material relating or implying to relate to a person, or suggesting it originated from a person

- monitoring or tracking when and how someone uses the internet, email or any other form of electronic communication, including frequent commenting or posting on someone’s social media profiles

- interfering with any property in the possession of a person

- watching or spying on a person.

7. Harmful practices

From 2020 government statutory guidance on Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) makes it compulsory for all secondary schools to teach pupils about female genital mutilation and other harmful practices, including forced marriage and ‘honour’ based abuse. There is no evidence to indicate that some cultural or ethnic groups are more abusive than others. Violence against women occurs in all cultures and across all socio-economic backgrounds. The differences are in the forms of violence and abuse. The harmful practices listed beloware human rights issues that affect everyone. Harmful practices result in gender inequality, aiming to control women and girls within the family and wider society. They have often been embedded in communities for a long time and are born out of community pressure. They include rituals, traditions or other practices that have a detrimental effect on the physical, mental and emotional health of the victim. In addition to the offences described in this section, other forms of harmful practice include breast flattening or ironing and child abuse linked to faith or belief.

‘Honour’ Based Abuse

So-called ‘Honour’ based abuse encompasses incidents or crimes committed to protect or defend the honour of the family and/or the community. Abuse committed to preserve ‘honour’ often involves a wider network of family or community pressure and can include multiple perpetrators. It is important to be aware of this dynamic and additional risk factors when deciding what form of safeguarding action to take. All forms of ‘honour’ based abuse are abuse (regardless of the motivation) and should be handled and escalated as such. Professionals in all agencies and individuals, groups and communities need to be alert to the possibility of a child being at risk of or already having suffered ‘honour’ based abuse.

When activating local safeguarding procedures, there are existing national and local protocols for multi-agency liaison with police and children’s social care. ‘Honour’ based abuse is often linked to family members or acquaintances who mistakenly believe someone has brought shame to their family or community by doing something that is not in keeping with their culture.

For example, ‘honour’ based abuse might be committed against people who:

- become involved with a boyfriend or girlfriend from a different culture or religion

- want to get out of an arranged or forced marriage

- wear clothes or take part in activities that might not be considered traditional within a particular culture.

Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

FGM comprises all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs. It is illegal in the UK and a form of child abuse with long-lasting harmful consequences. FGM is mostly carried out on young girls between infancy and age 15. Where FGM has taken place, since 31 October 2015 there has been a mandatory reporting duty placed on teachers, social workers and health professionals that requires a different approach. FGM mandatory reporting duty for teachers Section 5B of the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 (as inserted by section 74 of the Serious Crime Act 2015) places a statutory duty upon teachers along with regulated health and social care professionals in England and Wales, to report to the police where they discover (either through disclosure by the victim or visual evidence) that FGM appears to have been carried out on a girl under 18. Those failing to report such cases will face disciplinary sanctions. It will be rare for teachers to see visual evidence, and they should not be examining pupils or students, but the same definition of what is meant by “to discover that an act of FGM appears to have been carried out” is used for all professionals to whom this mandatory reporting duty applies.

It is believed that FGM happens to try and reduce a women’s sexual pleasure or desire. It is also often performed to control female sexual desires to preserve a girls’ virginity. FGM and the beliefs associated around it reinforce gender inequality. FGM has become so ingrained in communities over the generations that it’s often difficult for girls, boys, mothers, and fathers to challenge it. Equally, the community and family pressure and the stigma girls face when refusing FGM can make it feel like girls have no choice but to undergo FGM. FGM has been a criminal offence in the UK since 1985. In 2003 it also became a criminal offence for UK nationals or permanent UK residents to take their child abroad to have FGM. Anyone found guilty of the offence faces a maximum penalty of 14 years in prison. If you receive a disclosure from a girl or see visual evidence of FGM it is your responsibility to report it to the police by calling 101 and follow safeguarding procedures at your school or college. It is your personal responsibility that can’t be passed onto anyone else, including your safeguarding lead. Refer to the Mandatory Reporting of Female Genital Mutilation GuidelinesReference:52.

You can also contact the NSPCC’s anonymous dedicated FGM helpline on 0800 028 3550 or email [email protected].

Forced Marriage

Forcing a person into a marriage is a crime in England and Wales. A forced marriage is one entered without the full and free consent of one or both parties and where violence, threats or any other form of coercion is used to cause a person to enter a marriage. Threats can be physical or emotional and psychological. A lack of consent can be where a person does not consent or where they cannot consent (if they have learning disabilities, for example). Nevertheless, some communities use religion and culture to coerce a person into marriage.

Schools and colleges can play an important role in safeguarding children from forced marriage. Forced marriages happen for lots of different reasons. Some parents justify marriage as protecting their children. Other families feel that their honour and reputation are at stake if they don’t choose whom their child marries. Sometimes forced marriages are formed for financial reasons. Forcing someone to marry against their will is a criminal offence and the maximum penalty for this is seven years imprisonmentReference:53. The Forced Marriage UnitReference:54 has published statutory guidance which focuses on the role of schools and colleges. School and college staff can contact the Forced Marriage Unit for advice or information.

8. Delivering activities to prevent gender-based abuse

Introduction

Tender has been designing and delivering healthy relationship workshops since 2003. The exercises outlined below are tried and tested methods of initiating discussion and opening up the topic of domestic abuse for exploration. The activities have been applied in a wide variety of settings with a broad spectrum of children and young people.

Ground rules

Agree on the ground rules before beginning work on the issue. Ask that everyone treats each other’s opinions respectfully. It may be useful for young people to come up with their own ground rules or group contract/agreement, as this will increase their willingness to adhere to them. Examples of useful ground rules can include taking ‘time out’ should you need to, listening carefully to the opinions of others and treating the subject with sensitivity. It is worth saying to the group that people react differently to sensitive subjects – sometimes by becoming quiet or sometimes even laughing. This might seem strange, but if someone is laughing, it may be because they are uncomfortable, not that they are not taking the subject seriously. As part of the introduction to each activity, it is important to mention confidentiality: ‘what is said in the room, stays in the room’. However, equally important is to remind students of the safeguarding responsibilities of professionals, that if they, or someone close to them, is in any kind of danger, then the information could not remain confidential to the lesson or activity. (See Disclosures for more details).

Facilitating discussions about gender-based abuse

Some groups of young people will include individuals that have experienced or witnessed gender-based abuse, so it is important that discussions are managed sensitively. For professionals using this toolkit, it is important to preclude discussion with a ‘health warning’. This should set the tone in terms of the seriousness of the topics, include information about who to speak to if someone is affected by the issue and reference to self care. A suggested outline is provided below as a guide:

“The subject of relationships can be difficult to talk about. It might cause some of you to feel uncomfortable, giggle, feel upset or bring up memories you don’t like to think about. If you feel you need some time away from the lesson, then please let me know. If you would like to talk about anything after the session, you are welcome to speak to (insert name of staff member).”

Young people should be free to express themselves, but some attitudes (for example victim blaming) may be upsetting for other participants or the staff delivering the activities or lesson. Professionals should aim for a balance that allows young people to contribute openly, yet constructively challenges negative attitudes. See ‘Common challenging statements’ for guidelines. Honest and open debate enables young people to come to their own positive conclusions. Often groups will be able to deal with negative attitudes effectively themselves, and these conclusions are more valuable when arrived at through their own discussions.

Language

It may be useful to agree acceptable language to be used in the group. One approach is to ask young people to give every word they know for something (words for ‘woman’ for example), then agree which ones will be used. This means that potentially negative and offensive words are named and agreed as unacceptable to the majority of the group and therefore weakens their capacity to disrupt the group. Amongst young people, the ‘domestic’ tag may distance young people from the subject, as it can imply that the abuse must be based in the home. Professionals can use terms such as ‘healthy and unhealthy relationships’ to avoid this. Tender have included a section on ‘Common Challenging Statements’ to support professionals in navigating comments that often arise from young people.

Peer Learning

The messaging around healthy relationships and gender equality is much stronger when heard from someone of a similar age; there is power in children and young people talking to each other. Consider how the activities could contribute to students engaging with one another, and discussing these issues respectfully. This develops a culture across the school where children can ask for help and promoting healthy relationships and gender equality is seen as a responsibility that they all share.

To ensure the core messages and values of Tender’s work are embedded throughout the school, participants could share their learning with other pupils. Tender’s projects encourage participants to become ambassadors for positive social change in their peer groups and communities, for example, projects could culminate in participants creating resources, presentations, performances or campaigns for their peers. Becoming an ambassador for this work and sharing the learning with peers is empowering for participants as it will give them ownership over the work and a stronger sense of self-worth and confidence.

Disclosures

The issue of confidentiality should be addressed as soon as possible with the group. The group should be informed about the limits of your ability to maintain confidentiality and what can happen to information they share within the lesson including naming the Safeguarding Lead/ Officer for the school. It should be made clear to young people that they will not be obliged to disclose their own experiences. None of these plans and resources require them to do so. Some people may be concerned about this possibility. Disclosures may occur so it is important that young people understand the need for confidentiality within the group. However, do explain to the group that if they disclose anything that makes you concerned for their welfare or that of someone else, you will need to share this information with other people who can help.

It is advisable to minimise the use of personal stories in workshops because they may derail the conversation by reducing a general issue to a single example. Additionally, it may also be unsafe to discuss real life stories in a group. However, students who do choose to share personal stories should not be criticised for doing so. It may be the first time they have spoken out. Those who wish to seek support are likely to do so outside of the lesson. Young people should be made aware of where they can go for help, including school staff, police and outside agencies – especially Childline (0800 1111).

When a young person discloses it is important to stay calm and listen carefully to what is said. Do not promise to keep secrets: find an appropriate early opportunity to explain that it is likely that the information will need to be shared with others. Allow the participant to continue at their own pace, only ask questions for clarification purposes (at all times avoid asking questions that suggest a particular answer), reassure the participant that they have done the right thing in telling you, tell them what you will do next and who the information will be shared with. Record in writing what was said using the participant’s own words as soon as possible (note date, time, any names mentioned and to whom the information was given and ensure that the record is signed and dated).

Support

Young people should be reminded of where they can access support or help if either they, or anyone they know, is worried, distressed or being harmed by any of the topics you discuss. This should happen in every lesson or activity that takes place on the issue of gender-based abuse, not just in the exercise that looks at this topic in more detail. Information about what support is available in the school or youth setting should be provided along with details about more general services like Childline (see ‘Support’ activity for more details of services). In addition, local services to the school or youth setting could be provided.

9. Common challenging statements

When exploring healthy and unhealthy relationships with young people, there are several common challenging statements you are likely to hear. It is useful to keep the following principles in mind when dealing with challenges. Ideally a group will be able to arrive at these themselves through guided discussion and participation in activities:

- The use of violence or abuse is a choice. If an abuser is capable of choosing to use abuse against certain people, or in certain settings, they are also capable of choosing not to.

- Choice means responsibility. The responsibility for abuse lies with the abuser and never with the victim.

- There is never any excuse for using violence against another unless in self-defence.

Violence and abuse in relationships is present in all social, cultural and ethnic groups. Research shows little difference in incidence rates across these groups.

“If someone hit me, I’d just hit them back.”

Young people often take the standpoint that they would not allow themselves to become victim-survivors. Whilst this attitude can be seen as positive and empowering, it can also have negative consequences. It may be useful to ask the question ‘OK you hit him, what happens next?’

Although it is positive that many young people feel they are on an equal footing, the severity and regularity of abuse still being experienced by young women suggests that inequality still exists. These beliefs may lead women into a false sense of security, thinking that they are not at risk. This attitude can also lead to victim blaming i.e. ‘I wouldn’t allow this, so anyone who does is weak and only has themselves to blame’.

Victim blaming attitudes are common amongst young people and must be challenged. The victim of violence is never to blame for the violence. Physical violence in relationships is rarely an isolated event. It usually occurs alongside other forms of abuse (e.g. trivial demands, sexual violence/coercion, isolation, threats, and financial control). This makes it difficult for the victim to find the confidence to leave. The covert nature of abuse means many victim- survivors feel people will not believe them or feel responsible for the violence and therefore ashamed.

“They must have done something to start it.”

Research has revealed that more than one in four people in the European Union believe that sexual intercourse without consent may be justified in certain circumstances, such as if the victim is drunk or under the influence of drugs; or voluntarily going home with someone, wearing revealing clothes, not saying “no” clearly or not fighting backReference:55.

Regardless of whether a victim-survivor has nagged, disrespected, flirted or cheated on a partner, they do not deserve to be abused. This is a tricky issue to get across to some young people.

The first response can be to question the idea that not everyone ‘disrespected’ or cheated on (use the example given by the participant) reacts in a violent way. This suggests that those who do are choosing to. The group can then be encouraged to think about other options that person has, such as leaving the relationship, if they are not happy in it. The core argument is choice and responsibility. The idea that someone who feels provoked has no responsibility for their actions should be challenged. In general, people who are violent to their partners are capable of controlling their actions but choose to use abuse as an effective means of getting what they want, whether they recognise this or not.

The myth that the victim might have done something to deserve abuse leaves the abusers unaccountable for their behaviour, blaming outside influences for the occurrence of violent acts. Most abusers are able to control themselves enough to only abuse in private settings, to not cause injuries where they will show and to only harm women or children. If they have enough self-control to abuse in a particular way or in a particular setting, they have enough control to walk away.

Victim-survivors experiencing or witnessing abuse can sometimes minimise the violence (e.g. “they only do it because I wouldn’t listen” or “they only do it when they’ve had a drink”) as a coping mechanism. Some will minimise because their abuser has systematically made them feel at fault or accused them of ‘provocation’. Others find it easier to excuse than to accept that they are in an abusive relationship. They may not even recognise what is happening to them or identify it as abuse.

This is a common situation among young people, who might not see more psychological forms of abuse, such as isolation or pressure to have sex, as being abusive. It is always worth discussing abuse in all its forms, as well as emphasising that any type of abuse is always the choice of the abuser, and never the victim.

“Women often ‘cry rape’.”

There are regularly news stories about women who have perverted the course of justice by falsely accusing men of rape. These stories have led many people to believe that this is a common problem. However:

- Only 3-4% of rape cases reported to the UK police are found or suspected to be falseReference:56.

- Few rape cases are reported: 5 in 6 victim-survivors (83%) did not report their experiences to the police, which means only one in six (17%) victim-survivors had told the policeReference:57.

- Even fewer make it to court, with a significant decline in prosecutions for rape cases and just 14% of survivors believing they would receive justice by reporting the crime (based on a survey or 491 survivors)Reference:58.

- Around 1% of reported rapes result in a convictionReference:59.

It is very difficult for victim-survivors of rape and sexual assault to talk about their experiences, especially if they have been closely linked to the perpetrator:

- 83% of those who are raped know the perpetrator prior to the attackReference:60.

- 13.6% of women who suffered sexual violence did not report it because they feared violence as a result of telling someoneReference:61.

Victim-survivors may be less likely to report the crime due to the common misconception that women often make false accusations about rape - 25% do not report it because they didn’t think they would be believedReference:62. Moreover, it is known that the trauma of being the victim of rape can also impact on memory and recall – which can be misunderstood as the victim lying about their case. A victim-survivor may retract a rape claim because:

- The stress and trauma caused or exacerbated by the investigation, particularly because of having to talk in detail about the incident.

- Of a desire to move on from what had happened, often intensified by feeling surprised and overwhelmed by the process of official police investigation.

- Of a concern for their own safety, or for the perpetrator’s own situation, particularly in cases with a domestic abuse overlap where the victim’s priority often was to put an end to the harmful behaviour, rather than a prosecution.

“They did it because they were drunk.”

Some perpetrators of domestic abuse and sexual violence are under the influence of alcohol when they are violent. The Institute of Alcohol Studies reportsReference:63 that alcohol plays a ‘compounding effect’ in incidences of domestic abuse. Although not causal, it offers the offender a 'shield' thereby enabling them to excuse their violent behaviour. This has to be considered when discussing the relationship between alcohol and domestic abuse.

As society often excuses deviant behaviour carried out under the influence of alcohol, some perpetrators drink before being violent as their actions are more likely to be excused and they are less likely to face the consequences. Numerous studies show that perpetrators are violent when drinking alcohol but also when they are not. It can increase the level of violence, acting as a disinhibitor; however, it is not a direct cause. Tender strongly supports the view that substances are not the cause of violent behaviour. The idea that violence and abuse are always a choice cannot be over-emphasised: alcohol is never an excuse.

“Violent people come from violent families.”

It is sometimes said that witnessing domestic abuse and sexual violence at a young age leads to ‘cycles of abuse’ that require targeted interventions to prevent future violence in later life. Whilst there is a clear need for support services for those who have witnessed or experienced abuse, the term ‘cycles of abuse’ can be misleading and, at times, damaging for this work. Why the term ‘cycles of abuse’ doesn’t help:

- It puts negative expectations and judgements on children who’ve experienced domestic abuse, when they actually need support in coming to terms with their experiences. E.g., young men can be frightened that they will become abusers.

- It doesn’t recognise that many children actively support their mothers during experiences of domestic violence.

- It doesn’t acknowledge the gendered nature of domestic and sexual abuse: most women who witness/experience violence as girls do not then use it as adult women.

- It doesn’t acknowledge that children are influenced by a variety of different people and factors (including other family members, friends, schools, popular figures and so on). Children who’ve witnessed domestic abuse don’t automatically become carbon copies of the abusing parent.

- Finally, and most importantly, the cycle of violence theory doesn’t acknowledge that people have a choice about whether to be abusive.

10. Activities

These activities are formatted so that you can see what the aim of the activity is, with a minimum suggested timing to allow exploration of the topic. When planning a lesson, it is important to consider the group size and room, the needs and strengths of the young people and the time restrictions. We have created a variety of activities for a large group of 100+ young people (perhaps in an assembly) and for smaller groups of between 5-20 young people.

Adaptations

Most of the activities can be adapted to use with both large and small groups. They are intended as a guide and can be adapted to look at specific topics that are particularly relevant to the children and young people you work with and/or based on the responses of the group. Ensure you leave enough time should there be challenging statements that need to be addressed or important conversation that needs space to develop. You can also choose to run one activity or choose 2-3, depending on practical considerations and the needs of the students. We would always suggest opening with an ice breaker and signposting to additional support or information.

Opening and closing activities

We’d always suggest a short game or “icebreaker” to build trust, develop group dynamics and enable young people to feel comfortable.

Establishing opening and closing practices or rituals for the lessons is an effective way to break the ice, build trust and self-esteem and create a sense of safety for the group. Consistency is key. Examples include beginning and ending each lesson with a game, opening and closing each lesson with “on a scale of 1 – 10; 1 being the lowest and 10 the highest – how are you feeling today?” Asking ‘what has been the most valuable learning for you today?’ or ‘what would your younger self have liked to know?’ are other ways of closing. Leave time at the end of the lesson to ‘check in’ with young people and answer any questions.

In addition, at the end of lesson or activities, participants should be reminded of where they can access support for anything that is upsetting, worrying or distressing them. This should be opportunities for support within the school or youth setting environment, as well as key support services such as Childline (see Support activity).

Context

These activities cover topics required in statutory RSE and they are focused on gender- based abuse. It may be that professionals want to remind students at the beginning of each of these activities what the value of learning about gender-based abuse is, or you may decide to weave these key learning points through the course of the activity.

Tender would summarise this as:

- With 29.3% in the UK experiencing violence in a relationship at some point in their lifeReference:64, being able to identify abuse, learn how to get support and challenge behaviours that condone gender-based abuse will keep women and girls safe.

- There is evidence that young people (16- 24 years old) are at the highest risk of experiencing domestic abuseReference:65, one of the most common forms of gender-based abuse, which means it is important that young people understand it.

- Research proves that low-level sexist comments or ideas, whether online or ‘in real life’ contribute to supporting attitudes and beliefs that can result in abusive and violent behaviours. By discussing these openly, we can contribute to a safe environment for all. In addition, professionals may want a print- out of the pyramid (see section Young People and Gender-Based Abuse) to hand out to demonstrate how behaviours escalate from beliefs.

- Equally professionals might want to encourage thoughts from the group as to why learning about topics relating to gender- based abuse might be useful in their current and future lives, perhaps at the close of the lesson to reinforce learning.

Limitations

The data provided in this report is accurate to the best of our knowledge as of August 2023. But wherever the figures have been updated, seem incorrect or the source link is unavailable, please get in touch with Tender as soon as possible. This Toolkit will be reviewed annually, and the authors will endeavour to update statements and statistics where new data and evidence are available.

The report is not guided by an exhaustive literature review. The statistics in this toolkit should be used in a descriptive rather than a prescriptive capacity. Please take steps to make sure that the statistics are shared and understood in the context of the studies from where they are derived, which are cited in footnotes and in the reference list at the end of this document.

The statistics used in this Toolkit are produced separately by different organisations, but each provides only a partial picture, owing to their research motivations and priorities. As the research design differs between sources and organisations, caution must be made while referring and using this information. The data are not directly comparable, since they are collected on different sources using different timescales and reference periods. They may not necessarily cover the same cohort of cases.

Wherever possible, the data has been supported with a detailed explanation to acknowledge other relevant considerations. Where such an explanation is not possible due to word limits, the data source has been linked appropriately for reference.

11. Activity 1 - Statistics Corner

Aim

To examine the prevalence of domestic abuse and sexual violence in the UK from an evidence-based perspective.

Minimum suggested timing

- 15 minutes

Group size

- 5 – 100+

Additional notes

Using this toolkit you can change the statistics to include the most relevant statistics to the group and/or discussion you are hoping to have. If you are delivering in an assembly you may want to create a short slide deck for each statistic.

Instructions (group size 5-30 young people)

Explain to the group that you are going to ask them several questions and assign a corner of the room or space to each answer. They will have to move to the corner that they think corresponds to the correct answer. Ask each question in turn. When young people have made their decisions and chosen a corner to go to, discuss with them how they arrived at their answers. Unpick the group’s answers. Find out how they feel when they hear the answer to each statistic. For example, are they surprised by the correct answer or did they know some of the answers before?

Instructions (group size 30+ young people)

Explain to the group that you are going to ask them several questions and ask them to either raise a hand or stand up (dependent on the physical capabilities of the group). They will have to respond to the correct answer. Ask each question in turn. When young people have made their decisions, invite individuals to share why they chose their answer. Unpick the group’s answers. Find out how they feel when they hear the answer to each statistic. For example, are they surprised by the correct answer, or did they know some of the answers before?

16-24

25-35

35-50

50+

Useful discussion/learning points:

- Defining/breaking down the term ‘domestic’ abuse – e.g it doesn’t just happen in long- term relationships/marriages where people live together etc.

- Please highlight that this is an issue that doesn’t discriminate. Anyone can be affected by domestic violence/abuse no matter their age or background (no group experiences it more than another, i.e. not just people living in poverty, BAMER, etc.) But young people are most at risk.

- Why do you think young people are most at risk? Explore that young people are more likely to make unsafe and risky decisions and lack relationship experience.

30%

15%

65%

50%

Useful discussion/learning points:

-

As of the latest data available for England and Wales, the prevalence of any domestic abuse among adults since the age of 16 is recorded at 29.3% for women and 14.1% for men. In the year ending March 2022, women experienced more than twice as much as incidences of domestic abuse compared to men. (ONS, 2022). According to the same source, the experience of violence could have different impacts on men and women. Although, similar levels were reported for men and women on most physical and non-physical consequences after the most recent incident of rape or assault by penetration, women (63%) reported higher mental or emotional impact than men (47%). Men (39.2%), on the other hand, experienced higher levels of physical injuries than women (35.7%), particularly cases of severe bruising and scratches. However, the same figures for partner abuse tells a slightly different story. Men reported experiencing higher non-physical impact, particularly significantly higher levels of mental and emotional problems, as compared to women as a result of partner abuse experienced in the year ending March 2022 (Partner abuse in detail, 2022, Table 8). On the same note, women experienced more physical injuries (15.2%) due to partner abuse compared to men (9.4%).

-

Please ensure that you also acknowledge that violence and abuse can also happen in same-sex relationships - 49% of gay men have experienced at least one incident of domestic abuse from a family member or partner since the age of 16 (Domestic Abuse: Stonewall Health BriefingReference:69, Stonewall, 2013, p.5. Based on a survey of 6.861 respondents from across Britain). Furthermore, more than a quarter of trans people (28%) in a relationship in the last year have faced domestic abuse from a partner (Bachmann and Gooch 2018, p.6, based on a survey of 871 trans and/or non-binary people). Research conducted by GalopReference:70 in 2018 (Magić and Kelley, 2018, p.11) based on a sample of 626 unique LGBT+ victim/survivors found that the gender of perpetrators in relationship abuse was as follows: 71% of individual perpetrators were identified as male and 29% as female. The same study finds that 65% of victims/survivors in their sample were men. The Galop study concluded that men could be more likely to disclose more violent forms of abuse. It also added that due to the public discourse surrounding domestic abuse that mainly presents DA as an issue involving heterosexual men and women, gay men would be more inclined to seek help from LGBT+ organisations than mainstream ones. These nuances should be considered while discussing this data. While discussing Q2, ensure that the available statistic of violence experienced by LGBT+ individuals is also explained with the above supporting information. Note that the sample sizes in the Bachmann and Gooch and Galop studies: as the sizes are small, these statistics should be used as indicative examples rather than representative of national rates of prevalence.

2 / week

1 / week

1 / month

2 / month

Useful discussion/learning points:

-

Over one hundred women are killed each year in England and Wales by their current or former partnerReference:72. Make sure that the group have heard and understood this statistic and don’t just celebrate choosing the correct answer!

-

These statistics are predominately looking at male violence against women resulting in domestic homicide. This is because there is a disproportionate amount of male to female violence. According to the recent Office for National Statistics data (referenced in footnote 73), the reported number of female victims and male victims of domestic homicides where the suspect is a male partner or ex-partner is 207 and 6 respectively. To compare, the number of female victims and male victims of domestic homicide where the suspect is a female partner or ex-partner is 3 and 29 respectively. The data therefore indicates that the majority (72.1%) of the victims of domestic homicides were female and of those cases, most of the suspects were male (96.7%). By contrast, the majority of victims of non-domestic homicides were found to be male (87.6%).

-

There are important differences between male violence against women and female violence against men, namely the amount, severity and impact. Women experience higher rates of repeated victimisation and are much more likely to be seriously hurt or killed than male victim-survivors of domestic abuse. Further to that, women are more likely to experience higher levels of fear and are more likely to be subjected to coercive and controlling behaviours. It is important to acknowledge that domestic abuse does not discriminate and can affect anyone, and as noted earlier in this document, data suggests that male victims may be less likely to tell anyone about the abuse they experience.

12. Activity 2: Have A Word With Yourself, And Then Your Mates Video

Aim

To begin discussions around the impact of misogynistic and problematic language towards women and the impact of sexual harassment.

Minimum suggested timing:

- 20 minutes - Film running time: 1 minute 52 seconds

Group size:

- 5 – 100+

Additional notes:

You can show this to any group size as a conversation starter and develop the situation further by asking young people to create scenes or advice they may give to the characters we see in the film. Before the film we would suggest sharing statistics about gender-based violence and you could also run Temperature line (see below) or Word Tennis to bring some relevant language into the room and support young people to articulate what they see in the film.

Instructions (group size 5-30 young people):

Before the film invite young people to comment if they have seen the campaign and what they thought. Also have some still images of the campaign to show and ask what they think it’s trying to encourage people to do. Let the group know you are going to ask them some questions afterwards so watch carefully.

Severity and impact - Women experience higher rates of repeated victimisation and are much more likely to be seriously hurt or killed than male victim-survivors of domestic abuse. Further to that, women are more likely to experience higher levels of fear and are more likely to be subjected to coercive and controlling behaviours (Women’s Aid, 2020).

After showing the film, here are some questions you could ask:

- What did you see happening in the film?

- Where do you think the group of friends had been before they went to the shop?

- Where might the pair of friends have been before?

- Why do you think the character in the cream coat approached the young woman sitting on the bench?

- What words would you use to describe what’s happening?

- How does the young woman feel when she is with her friend?

- How does the young woman feel when she is approached by the group?

- How does the young woman feel when she gets in the cab?

- Who has the most power in that situation and how can you tell that?

- What is the character in the cream coat feeling?

- What do you think about how Jacob handles that situation?

- What could Jacob say to his friend after they leave?

- Do you think this happens often?

- Where else does it happen?

- Why do you think it’s happening?

- Why do some people want to have more power and control over others?

- Is this sort of behaviour ever ok or excusable?

- Is this sort of behaviour legal?

- What do you think the young woman will do when she gets home?

- What would you say to the young woman if you were her friend?

- What could the young woman do to get help and support after that?

There may be other questions or thoughts the group share afterwards, encourage students in the group to support each other in having a conversation. You could also ask the whole group to vote on certain questions, such as “Who here has seen something similar to this?”. We would never ask a group to share if they have experienced or perpetrated this behaviour.

Key learning points:

- This film shows misogynistic behaviour and sexual harassment that is designed to intimidate and humiliate.

- Male violence against women and girls starts with words.

- We are all responsible for stopping misogynistic behaviour.

- If you see it happening, say something.

13. Activity 3: Temperature line

Aim

To begin discussions around the positive and/or negative understandings of different behaviours.

Minimum suggested timing:

- 20 minutes

Group size:

- 5 – 100+

Additional notes:

You can incorporate words that use language you have heard young people use or themes you know are particularly relevant to them. Be mindful of triggering any upsetting experiences. The below instructions are best delivered in a classroom setting. To deliver temperature line in an assembly/larger group we would suggest the professional holds up a smaller amount of words and invites the young people to share their opinion of where they should go on the line and invite others to contribute to this. You can either use a slide deck to write the words up or a Google JamBoard, or alternatively you can invite young people to come and stand/sit on a chair at the front holding the word. Be mindful of anyone standing at the front for long periods of time.

Instructions (group size 5-30 young people):

Using the given words on A4 paper (see Appendix: Resources, Temperature line words), make an imaginary line down the centre of the room, stating that ‘healthy’ is at one end and ‘unhealthy’ at the other. Give individuals or pairs a few of the words and ask them to place these on the line, depending on how healthy or unhealthy they think that word is in the context of an intimate relationship (e.g. boyfriend/ girlfriend). For example, a participant may put ‘kicking’ near the unhealthy end of the line and ‘kissing’ near the healthy end.