Key information

Publication type: The London Plan

Publication date:

Contents

17 sections

Policy SI 1 Improving air quality

9.1.1 Poor air quality is a major issue for London which is failing to meet requirements under legislation. Poor air quality has direct impacts on the health, quality of life and life expectancy of Londoners. The impacts tend to be most heavily felt in some of London’s most deprived neighbourhoods, and by people who are most vulnerable to the impacts, such as children and older people. London’s air quality should be significantly improved and exposure to poor air quality, especially for vulnerable people, should be reduced.

9.1.2 The Mayor is committed to making air quality in London the best of any major world city, which means not only achieving compliance with legal limits for Nitrogen Dioxide as soon as possible and maintaining compliance where it is already achieved, but also achieving World Health Organisation targets for other pollutants such as Particulate Matter.

9.1.3 The aim of this policy is to ensure that new developments are designed and built, as far as is possible, to improve local air quality and reduce the extent to which the public are exposed to poor air quality. This means that new developments, as a minimum, must not cause new exceedances of legal air quality standards, or delay the date at which compliance will be achieved in areas that are currently in exceedance of legal limits.[148] Where limit values are already met, or are predicted to be met at the time of completion, new developments must endeavour to maintain the best ambient air quality compatible with sustainable development principles.

9.1.4 Where this policy refers to ‘existing poor air quality’ this should be taken to include areas where legal limits for any pollutant, or World Health Organisation targets for Particulate Matter, are already exceeded and areas where current pollution levels are within 5 per cent of these limits.[149]

9.1.5 For major developments, a preliminary Air Quality Assessment should be carried out before designing the development to inform the design process. The aim of a preliminary assessment is to assess:

- The most significant sources of pollution in the area

- Constraints imposed on the site by poor air quality

- Appropriate land uses for the site

- Appropriate design measures that could be implemented to ensure that development reduces exposure and improves air quality.

9.1.6 Further assessments should then be carried out as the design evolves to ensure that impacts from emissions are prevented or minimised as far as possible, and to fully quantify the expected effect of any proposed mitigation measures, including the cumulative effect where other nearby developments are also underway or likely to come forward.

9.1.7 Assessment of the impacts of a scheme on local air pollution should include fixed plant, such as boiler and emergency generators, as well as expected transport-related sources. The impact assessment part of an Air Quality Assessment should always include all relevant pollutants. Industrial, waste and other working sites may need to include on-site vehicles and mobile machinery as well as fixed machinery and transport sources.

9.1.8 The impact assessment should provide decision makers with sufficient information to understand the scale and geographic scope of any detrimental, or beneficial, impacts on air quality and enable them to exercise their professional judgement in deciding whether the impacts are acceptable, in line with best practice.

9.1.9 Meeting the Air Quality Neutral benchmarks,[150] although necessary to control the growth in London’s regional emissions, will not always be sufficient to prevent unacceptable local impacts, as these may be affected by other factors, such as the location of the emissions source, the rate of emissions (as opposed to the annual quantum) and the layout of the development in relation to the surrounding area. As developments can still have significant local impacts that are not captured by Air Quality Neutral, for example by concentrating emissions, increasing exposure or preventing dispersion in particular locations, it is still important for these impacts to be assessed and mitigated.

9.1.10 For most minor developments, achieving Air Quality Neutral will be enough to demonstrate that they are in accordance with Part B1 of this policy. However, where characteristics of the development or local features raise concerns about air quality, or where there are additional requirements for assessment in local policy, a full Air Quality Assessment may be required. Additional measures may also be needed to address local impacts. Guidance on Air Quality Neutral will set out streamlined assessment procedures for minor developments.

9.1.11 An air quality positive approach is linked to other policies in the London Plan, such as Healthy Streets, energy masterplanning and green infrastructure. One of the keys to delivering this will be to draw existing good practice together in a holistic fashion, at an early stage in the process, to ensure that the development team can identify which options deliver the greatest improvement to air quality. Large schemes, subject to Environmental Impact Assessments, commonly have project and design teams representing a range of expertise, that can feed in to the development of a statement to set out how air quality can be improved across the proposed area of the development.

9.1.12 Single-site schemes, including referable schemes, are often constrained by pre-existing urban form and structure, transport and heat networks. These constraints may limit their ability to consider how to actively improve local air quality. By contrast, large schemes, particularly masterplans, usually have more flexibility to consider how new buildings, amenity and public spaces, transport and heat networks are deployed across the area and will therefore have greater opportunities to improve air quality and reduce exposure through the careful choice of design and infrastructure solutions. Delivery of an air quality positive approach will be project specific and will rely on the opportunities on site or in the surrounding area to improve air quality.

9.1.13 Statements for large-scale development proposals, prepared in response to Part C of this policy, should set out:

- How air quality is intended to be analysed and opportunities for its improvement identified as part of the design process.

- How air quality improvements have informed the design choices made about layout and distribution of buildings, amenity spaces and infrastructure.

- What steps will be taken to promote the uptake and use of sustainable and zero-emission modes of transport beyond minimum requirements. This may include specific measures in transport plans or delivery against Healthy Streets indicators.

- How air pollutant emissions from the buildings or associated energy centres can be reduced beyond the minimum requirements set out in Part B of this policy. This may include specific measures in heating masterplans or working with existing heat network providers to reduce or eliminate energy centre emissions.

- How specific measures that are identified to deliver air quality improvements will be evaluated and secured, including whether more detailed design specifications will be required so that the final development meets the desired performance.

9.1.14 The GLA will produce guidance in order to assist developers and boroughs in identifying measures and best practice to inform the preparation of statements for developments taking an air quality positive approach.

9.1.15 Where the Air Quality Assessment or the air quality positive approach assumes that specific measures are put in place to improve air quality, prevent or mitigate air quality impacts, these should be secured through the use of planning conditions or s106 agreements. For instance, if ultra-low NOx boilers are assumed in the assessment, conditions should require the provision of details of the installed plant prior to the occupation of the building, or where larger plant is used for heating, post installation emissions tests should be required to ensure that the modelled emission parameters are achieved.

9.1.16 The GLA maintains and publishes an inventory of emission sources (the London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory or LAEI). This inventory is based on a detailed assessment of all current sources of pollution in London and can be used to help understand the existing environment at development sites.

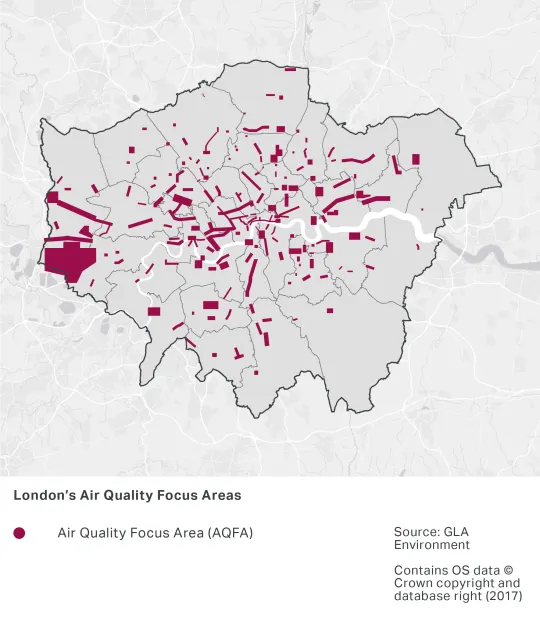

9.1.17 Air Quality Focus Areas (AQFA) are locations that not only exceed the EU annual mean limit value for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) but are also locations with high human exposure. AQFAs are not the only areas with poor air quality but they have been defined to identify areas where currently planned national, regional and local measures to reduce air pollution may not fully resolve poor air quality issues. There are currently 187 AQFAs across London (Figure 9.1). The list of Air Quality Focus Areas is updated from time to time as the London Atmospheric Inventory is reviewed and the latest list in the London Datastore should always be checked.

9.1.18 AQFAs are distinct from Air Quality Management Areas. Air Quality Management Areas (AQMAs) are declared by the London boroughs in response to modelled or measured existing exceedances of legal air quality limits. The analysis underpinning AQMAs is often more spatially detailed than London-wide modelling and may include the identification of additional air quality hot spots or other local issues.

9.1.19 All London boroughs have declared AQMAs covering some or all of their area. Boroughs are required to produce Air Quality Action Plans setting out the actions they are taking to improve local air quality; planning decisions should be in accordance with these action plans and developers should take any local requirements in Air Quality Action Plans into account.

9.1.20 AQFAs are defined based on GLA modelling forecasts that incorporate actions taken by the GLA and others as well as broader changes in emissions sources and are not intended to supplant the role of AQMAs in planning decisions. In practice developers will need to consider both designations where they overlap.

9.1.21 It may not always be possible in practice for developments to achieve Air Quality Neutral standards or to acceptably minimise impacts using on-site measures alone. If a development can demonstrate that it has exploited all relevant on-site measures it may be possible to make the development acceptable through additional mitigation or offsetting payments.

9.1.22 Where there have been significant improvements to air quality resulting in an area no longer exceeding air quality limits, Development Plans should not take advantage of this investment and worsen the local air quality back to a poor level. The sustainability appraisal for local plans should consider the effect of national, London-wide and local programmes to improve air quality to ensure that any potential conflicts are avoided.

9.1.23 Further guidance will be published on Air Quality Neutral and air quality positive approaches as well as guidance on how to reduce construction and demolition impacts.

Figure 9.1 - Air Quality Focus Areas

Policy SI 2 Minimising greenhouse gas emissions

9.2.1 The Mayor is committed to London becoming a zero-carbon city. This will require reduction of all greenhouse gases, of which carbon dioxide is the most prominent.[153] London’s homes and workplaces are responsible for producing approximately 78 per cent of its greenhouse gas emissions. If London is to achieve its objective of becoming a zero-carbon city by 2050, new development needs to meet the requirements of this policy. Development involving major refurbishment should also aim to meet this policy.

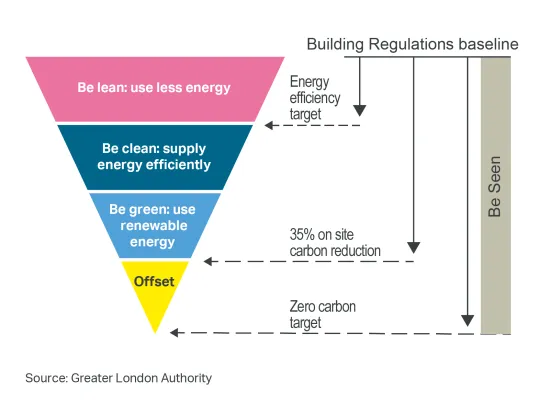

9.2.2 The energy hierarchy (Figure 9.2) should inform the design, construction and operation of new buildings. The priority is to minimise energy demand, and then address how energy will be supplied and renewable technologies incorporated. An important aspect of managing demand will be to reduce peak energy loadings.

9.2.3 Boroughs should ensure that all developments maximise opportunities for on-site electricity and heat production from solar technologies (photovoltaic and thermal) and use innovative building materials and smart technologies. This approach will reduce carbon emissions, reduce energy costs to occupants, improve London’s energy resilience and support the growth of green jobs.

9.2.4 A zero-carbon target for major residential developments has been in place for London since October 2016 and applies to major non-residential developments on final publication of this Plan.

Figure 9.2 - The energy hierarchy and associated targets

9.2.5 To meet the zero-carbon target, an on-site reduction of at least 35 per cent beyond the baseline of Part L of the current Building Regulations is required.[154] The minimum improvement over the Target Emission Rate (TER) will increase over a period of time in order to achieve the zero-carbon London ambition and reflect the costs of more efficient construction methods. This will be reflected in future updates to the London Plan.

9.2.6 The Mayor recognises that Building Regulations use outdated carbon emission factors and that this will continue to cause uncertainty until they are updated by Government. Interim guidance has been published in the Mayor’s Energy Planning Guidance on the use of appropriate emissions factors. This guidance will be updated again once Building Regulations are updated to help provide certainty to developers on how these policies are implemented.

9.2.7 Developments are expected to achieve carbon reductions beyond Part L from energy efficiency measures alone to reduce energy demand as far as possible. Residential development should achieve 10 per cent and non-residential development should achieve 15 per cent over Part L. Achieving energy credits as part of a Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) rating can help demonstrate that energy efficiency targets have been met. Boroughs are encouraged to include BREEAM targets in their Local Plans where appropriate.

9.2.8 The price for offsetting carbon[155] is regularly reviewed. Changes to the GLA’s suggested carbon offset price will be updated in future guidance. New development is expected to get as close as possible to zero-carbon on-site, rather than relying on offset fund payments to make up any shortfall in emissions. However, offset funds have the potential to unlock carbon savings from the existing building stock through energy efficiency programmes and by installing renewable technologies – typically more expensive to deliver in London due to the building age, type and tenure.

9.2.9 The Mayor provides support to boroughs by advising those which are at the early stages of setting up their carbon offsetting funds, and by setting out guidance on how to select projects. To ensure that offset funds are used effectively to reduce carbon whilst encouraging a holistic approach to retrofitting, Mayoral programmes offer additional support.[156]

9.2.10 The move towards zero-carbon development requires comprehensive monitoring of energy demand and carbon emissions to ensure that planning commitments are being delivered. Major developments are required to monitor and report on energy performance, such as by displaying a Display Energy Certificate (DEC), and reporting to the Mayor for at least five years via an online portal to enable the GLA to identify good practice and report on the operational performance of new development in London.

9.2.11 Operational carbon emissions will make up a declining proportion of a development’s whole life-cycle carbon emissions as operational carbon targets become more stringent. To fully capture a development’s carbon impact, a whole life-cycle approach is needed to capture its unregulated emissions (i.e. those associated with cooking and small appliances), its embodied emissions (i.e. those associated with raw material extraction, manufacture and transport of building materials and construction) and emissions associated with maintenance, repair and replacement as well as dismantling, demolition and eventual material disposal). Whole life-cycle carbon emission assessments are therefore required for development proposals referable to the Mayor. Major non-referable development should calculate unregulated emissions and are encouraged to undertake whole life-cycle carbon assessments. The approach to whole life-cycle carbon emissions assessments, including when they should take place, what they should contain and how information should be reported, will be set out in guidance.

9.2.12 The Mayor may publish further planning guidance on sustainable design and construction[157] and will continue to regularly update the guidance on preparing energy strategies for major development. Boroughs are encouraged to request energy strategies for other development proposals where appropriate. As a minimum, energy strategies should contain the following information:

a. a calculation of the energy demand and carbon emissions covered by Building Regulations and, separately, the energy demand and carbon emissions from any other part of the development, including plant or equipment, that are not covered by the Building Regulations (i.e. the unregulated emissions), at each stage of the energy hierarchy

b. proposals to reduce carbon emissions beyond Building Regulations through the energy efficient design of the site, buildings and services, whether it is categorised as a new build, a major refurbishment or a consequential improvement

c. proposals to further reduce carbon emissions through the use of zero or low-emission decentralised energy where feasible, prioritising connection to district heating and cooling networks and utilising local secondary heat sources. (Development in Heat Network Priority Areas should follow the heating hierarchy in Policy SI 3 Energy infrastructure)

d. proposals to further reduce carbon emissions by maximising opportunities to produce and use renewable energy on-site, utilising storage technologies where appropriate

e. proposals to address air quality risks (see Policy SI 1 Improving air quality). Where an air quality assessment has been undertaken, this could be referenced instead

f. the results of dynamic overheating modelling which should be undertaken in line with relevant Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) guidance, along with any mitigating actions (see Policy SI 4 Managing heat risk)

g. proposals for demand-side response, specifically through installation of smart meters, minimising peak energy demand and promoting short-term energy storage, as well as consideration of smart grids and local micro grids where feasible

h. a plan for monitoring and annual reporting of energy demand and carbon emissions post-construction for at least five years

i. proposals explaining how the site has been future-proofed to achieve zero-carbon on-site emissions by 2050

j. confirmation of offsetting arrangements, if required

k. a whole life-cycle carbon emissions assessment, and actions to reduce life-cycle carbon emissions (for development proposals referable to the Mayor)

l. analysis of the expected cost to occupants associated with the proposed energy strategy

m. proposals that connect to or create new heat networks should include details of the design and specification criteria and standards for their systems as set out in Policy SI 3 Energy infrastructure.

Policy SI 3 Energy infrastructure

9.3.1 The Mayor will work with boroughs, energy companies and major developers to promote the timely and effective development of London’s energy system (energy production, distribution, storage, supply and consumption).

9.3.2 London is part of a national energy system and currently sources approximately 95 per cent of its energy from outside the GLA boundary. Meeting the Mayor’s zero-carbon target by 2050 requires changes to the way we use and supply energy so that power and heat for our buildings and transport is generated from local clean, low-carbon and renewable sources. London will need to shift from its reliance on using natural gas as its main energy source to a more diverse range of low and zero-carbon sources, including renewable energy and secondary heat sources. Decentralised energy and local secondary heat sources will become an increasingly important element of London’s energy supply and will help London become more self-sufficient and resilient in relation to its energy needs.

9.3.3 Many of London’s existing heat networks have grown around combined heat and power (CHP) systems. However, the carbon savings from gas engine CHP are now declining as a result of national grid electricity decarbonising, and there is increasing evidence of adverse air quality impacts. Heat networks are still considered to be an effective and low-carbon means of supplying heat in London, and offer opportunities to transition to zero-carbon heat sources faster than individual building approaches. Where there remains a strategic case for low-emission CHP systems to support area-wide heat networks, these will continue to be considered on a case-by-case basis. Existing networks will need to establish decarbonisation plans. These should include the identification of low- and zero-carbon heat sources that may be utilised in the future, in order to be zero-carbon by 2050. The Mayor will consider how boroughs and network operators can be supported to achieve this.

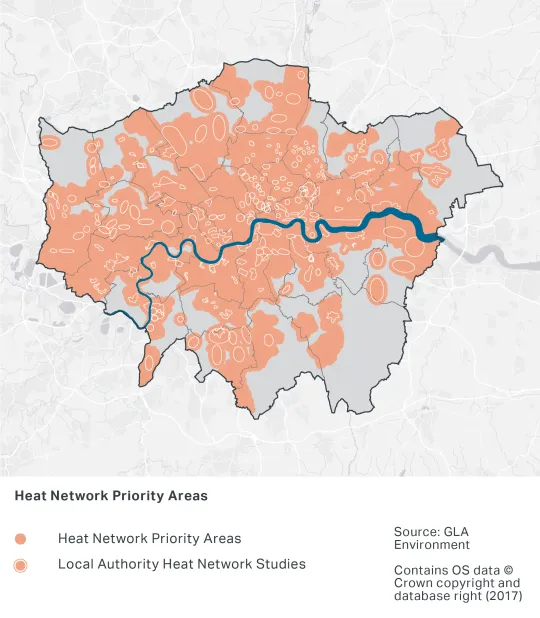

9.3.4 Developments should connect to existing heat networks wherever feasible. New and existing networks should incorporate good practice design and specification standards comparable to those set out in the CIBSE/ADE Code of Practice CP1 for the UK or equivalent. They should also register with the Heat Trust or an equivalent scheme. This will support the development of good quality networks whilst helping network operators prepare for regulation and ensuring that customers are offered a reliable, cost-competitive service. Stimulating the delivery of new district heating infrastructure enables the opportunities that district heating can provide for London’s energy system to be maximised. The Mayor has identified Heat Network Priority Areas, which can be found on the London Heat Map website.[158] These identify where in London the heat density is sufficient for heat networks to provide a competitive solution for supplying heat to buildings and consumers. Data relating to new and expanded networks will be regularly captured and made publicly available. Major development proposals outside Heat Network Priority Areas should select a low-carbon heating system that is appropriate to the heat demand of the development, provides a solution for managing peak demand, as with heat networks, and avoids high energy bills for occupants.

9.3.5 Where developments are proposed within Heat Network Priority Areas but are beyond existing heat networks, the heating system should be designed to facilitate cost-effective future connection. This may include, for example, allocating space in plant rooms for heat exchangers and thermal stores, safeguarding suitable routes for pipework from the site boundary and making provision for connections to the future network at the site boundary. The Mayor is taking a more direct role in the delivery of district-level heat networks so that more new and existing communally-heated developments will be able to connect into them, and has developed a comprehensive decentralised energy support package. Further details are available in the London Environment Strategy.

9.3.6 The Mayor also supports the development of low-temperature networks for both new and existing systems as this allows cost-effective use of low-grade waste heat. It is expected that network supply temperatures will drop from the traditional 90°C-95°C to 70°C and less depending on system design and the temperature of available heat sources. Further guidance on designing and operating heat networks will be set out in the updated London Heat Network Manual.

9.3.7 Low-emission CHP in this policy refers to those technologies which inherently emit very low levels of NOx. It is not expected that gas engine CHP will fit this category with the technology that is currently available. Further details on circumstances in which it will be appropriate to use low-emission CHP and what additional emissions monitoring will be required will be provided in further guidance. This guidance will be regularly updated to ensure that it reflects changes in technology.

Figure 9.3 - Heat Network Priority Areas

9.3.8 Increasing the amount of renewable and secondary energy is supported and development proposals should identify opportunities to maximise both secondary heat sources and renewable energy production on-site. This includes the use of solar photovoltaics, heat pumps and solar thermal, both on buildings and at a larger scale on appropriate sites. There is also potential for wind and hydropower-based renewable energy in some locations within London. Innovative low- and zero-carbon technologies will also be supported.

9.3.9 Electricity is essential for the functioning of any modern city. Demand is expected to rise in London in response to a growing population and economy, the increased take up of electric vehicles, and the switch to electric heating systems (such as through heat pumps). It is of concern that the electricity network and substations are at or near to capacity in a number of areas, especially in central London. The Mayor will work with the electricity and heat industry, boroughs and developers to ensure that appropriate infrastructure is in place and integrated within a wider smart energy system designed to meet London’s needs.

9.3.10 Demand for natural gas in London has been decreasing over the last few years, with a 25 per cent reduction since 2000.[159] This trend is expected to continue due to improved efficiency and a move away from individual gas boilers. Alongside the continuing programme of replacing old metal gas mains (predominantly with plastic piping), local infrastructure improvements may be required to supply energy centres, associated with heat networks, that will support growth in Opportunity Areas and there may also be a requirement for the provision of new pressure reduction stations. These requirements should be identified in energy masterplans.

9.3.11 Cadent Gas and SGN operate London’s gas distribution network. Both companies are implementing significant gasholder de-commissioning programmes, replacing them with smaller gas pressure reduction stations. The Mayor will work with key stakeholders including the Health and Safety Executive to achieve the release of the resulting brownfield sites for redevelopment including energy infrastructure where appropriate.

9.3.12 Land will be required for energy supply infrastructure including energy centres. These centres can capture and store energy as well as generate it. The ability to efficiently store energy as well as to generate it can reduce overall energy consumption, reduce peak demand and integrate greater levels of renewable energy into the energy system.

Policy SI 4 Managing heat risk

9.4.1 Climate change means London is already experiencing higher than historic average temperatures and more severe hot weather events. This, combined with a growing population, urbanisation and the urban heat island effect, means that London must manage heat risk in new developments, using the cooling hierarchy set out above. Whilst the cooling hierarchy applies to major developments, the principles can also be applied to minor development.

9.4.2 In managing heat risk, new developments in London face two challenges – the need to ensure London does not overheat (the urban heat island effect) and the need to ensure that individual buildings do not overheat. The urban heat island effect is caused by the extensive built up area absorbing and retaining heat during the day and night leading to parts of London being several degrees warmer than the surrounding area. This can become problematic on the hottest days of the year as daytime temperatures can reach well over 30⁰C and not drop below 18⁰C at night. These circumstances can lead many people to feel too hot or not be able to sleep, but for those with certain health conditions, and ‘at risk’ groups such as some young or elderly Londoners, the effects can be serious and worsen health conditions. Green infrastructure can provide some mitigation of this effect by shading roof surfaces and through evapotranspiration. Development proposals should incorporate green infrastructure in line with Policy G1 Green infrastructure and Policy G5 Urban greening.

9.4.3 Many aspects of building design can lead to increases in overheating risk, including high proportions of glazing and an increase in the air tightness of buildings. Single-aspect dwellings are more difficult to ventilate naturally and are more likely to overheat, and should normally be avoided in line with Policy D6 Housing quality and standards. There are a number of low-energy measures that can mitigate overheating risk. These include solar shading, building orientation and solar-controlled glazing. Occupant behaviour will also have an impact on overheating risk. The Mayor’s London Environment Strategy sets out further detail on actions being taken to address this.

9.4.4 Passive ventilation should be prioritised, taking into account external noise and air quality in determining the most appropriate solution. The increased use of air conditioning systems is not desirable as these have significant energy requirements and, under conventional operation, expel hot air, thereby adding to the urban heat island effect. If active cooling systems, such as air conditioning systems, are unavoidable, these should be designed to reuse the waste heat they produce. Future district heating networks are expected to be supplied with heat from waste heat sources such as building cooling systems.

9.4.5 The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers (CIBSE) has produced guidance on assessing and mitigating overheating risk in new developments, which can also be applied to refurbishment projects. TM 59 should be used for domestic developments and TM 52 should be used for non-domestic developments. In addition, TM 49 guidance and datasets should also be used to ensure that all new development is designed for the climate it will experience over its design life. Further information will be provided in guidance on how these documents and datasets should be used.

Policy SI 5 Water infrastructure

9.5.1 Londoners consume on average 149 litres of water per person per day – around 8 litres above the national average. All water companies that serve London are located in areas classified as seriously water-stressed. London is at risk of drought after two dry winters. During 2006 and 2012 water use restrictions affecting London were imposed. These restrictions were limited to sprinkler, hosepipe and non-essential user bans. A severe drought – with rota cuts, standpipes, reduced mains pressure or adding non-potable water to the mains supply – would have major implications for Londoners’ health and wellbeing, the environment and London’s economy. The Mayor will work with the water industry to prevent this level of water restriction being required for London in future.

9.5.2 An important aspect of avoiding the most severe water restrictions is to ensure that leakage is reduced and water used as efficiently as possible. The Optional Requirement set out in Part G of the Building Regulations should be applied across London.[161] A fittings-based approach should be used to determine the water consumption of a development. This approach is transparent and compatible with developers’ procurement and the emerging Water Label,[162] which Government and the water companies serving London are supporting.

9.5.3 Even with increased water efficiency and reduced leakage, water companies are forecasting an increasing demand for water. Without additional sources of supply, the increased demand will increase the risk of requiring water restrictions during drought periods. Security of supply should be ensured. Demand forecasts need to continue to be monitored and based on the consistent use of demographic data across spatial and infrastructure planning regimes.

9.5.4 Thames Water has set out through the water resource management planning process its preferred approach to strategic water supply options to serve London and parts of the Wider South East. It is considering a suite of options, including a potential new reservoir, effluent reuse, water transfers and new groundwater sources.

9.5.5 A strategic approach to water supply networks to ensure future water resilience and, in particular, the timely planning for a new strategic water resource to serve London and the Wider South East is important. In its draft Water Resource Management Plan, Thames Water has explored coordinated supply options with the other water companies serving London and the South East of England working with the Water Resource South East Group. Water Resource East has undertaken similar work in the East of England area. All this involves partnership working with key stakeholders within London and beyond its boundaries.

9.5.6 Infrastructure investment is constrained by the short-term nature of water companies’ investment plans. Similar to the approach to electricity supply, in order to facilitate the delivery of development it is important that investment in water supply infrastructure is provided ahead of need. To minimise wastage, water supply infrastructure improvements should give consideration to the replacement of ageing trunk mains.

9.5.7 In the context of the significant investment needed, measures to protect and support vulnerable customers in particular from rising water bills are important.

9.5.8 In relation to wastewater and improvements to the water environment, Water Framework Directive requirements should be maintained through the Thames River Basin Management Plan and the Catchment Plans prepared by the Catchment Partnerships, of which there are 12 in London. These Partnerships share lessons, experiences and best practice, and help achieve a coordinated approach to delivering the Thames River Basin Management Plan. Development Plans should be supported by evidence, which demonstrates that the development planned for:

a. will not compromise the Thames River Basin Management Plan objective of achieving ‘Good’ status, or cause deterioration in water quality; and

b. will be supported by adequate and timely provision of wastewater treatment infrastructure.

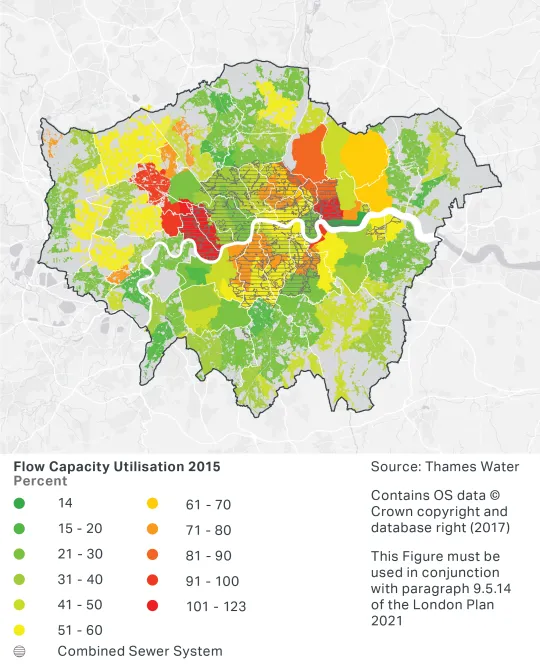

9.5.9 The Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive drives improvements in wastewater treatment infrastructure. Figure 9.4 provides a spatial illustration of the wastewater drainage capacity across London. Additional land may be required for upgrades or improvements at some wastewater treatment plants during the Plan period. Different wastewater treatment options may vary significantly in terms of their energy requirements, and there are significant opportunities for energy generation from wastewater treatment (sewage sludge).

9.5.10 The Thames Tideway Tunnel is under construction and will help to improve the water quality of the River Thames by significantly reducing the frequency of untreated sewage being discharged into the Thames (known as combined sewer overflows). Sustainable drainage measures are of particular importance in areas with sewer capacity limitations and their widespread implementation over the coming decades will help the resilience of London and avoid the need for further major sewer tunnel projects. Thames Water is taking a long-term approach to drainage and wastewater management planning. Its London 2100 plan will identify the most appropriate strategy for ensuring that London’s drainage and wastewater systems can meet the needs of London over the next 80 years in the most sustainable way.

9.5.11 London’s tributary rivers suffer significant pollution from misconnected sewers. This allows untreated sewage into what are often small streams, many of which flow through London’s parks and open spaces. Conversely, if surface water is misconnected to the foul system, sewer capacity issues are created within sewers and at sewage treatment works. Development proposals should therefore take action to minimise the potential for misconnections.

9.5.12 Development Plans and proposals should demonstrate that they have considered the opportunities for integrated solutions to water-related constraints and the provision of water infrastructure within strategically or locally defined growth locations. These could be Opportunity Areas or growth locations defined in Local Plans. Where such opportunities are identified, Development Plans should require an integrated and collaborative approach from developers. This could for example lead to the establishment of local water reuse systems or integrated drainage networks. Integration with the planning of green infrastructure could deliver further benefits.

9.5.13 A water advisory group with representatives from across the water sectors in London has been established to advise the Mayor and share information on strategic water and flood risk management issues across the capital.

Figure 9.4 - Spatial illustration of wastewater drainage capacity across London

Note for Figure 9.4: Thames Water has developed a model of its drains and sewers in London to assess waste water flows. The model compares the theoretical capacity of the drain or sewer pipe against how much waste water flow the pipe is currently receiving during a one in two-year rainfall event. The model’s outputs can be visualised as a ‘heat map’, which highlights at a strategic scale where there is a higher (green) or lower (red) ability to receive additional flows.‘Green’ areas do not mean that no additional drainage infrastructure is required. The modelling does not consider how waste water is routed through the network, so it should be noted that some ‘green’ areas will flow into ‘red’ areas, hence increasing flows upstream will exacerbate performance in the downstream catchments. The hatched area on the map shows the portions of the sewer system that are generally combined sewers, which means they capture both waste water and surface water flows.

Policy SI 6 Digital connectivity infrastructure

9.6.1 The provision of digital infrastructure is as important for the proper functioning of development as energy, water and waste management services and should be treated with the same importance. London should be a world-leading tech hub with world-class digital connectivity that can anticipate growing capacity needs and serve hard to reach areas. Fast, reliable digital connectivity is essential in today’s economy and especially for digital technology and creative companies. It supports every aspect of how people work and take part in modern society, helps smart innovation and facilitates regeneration.

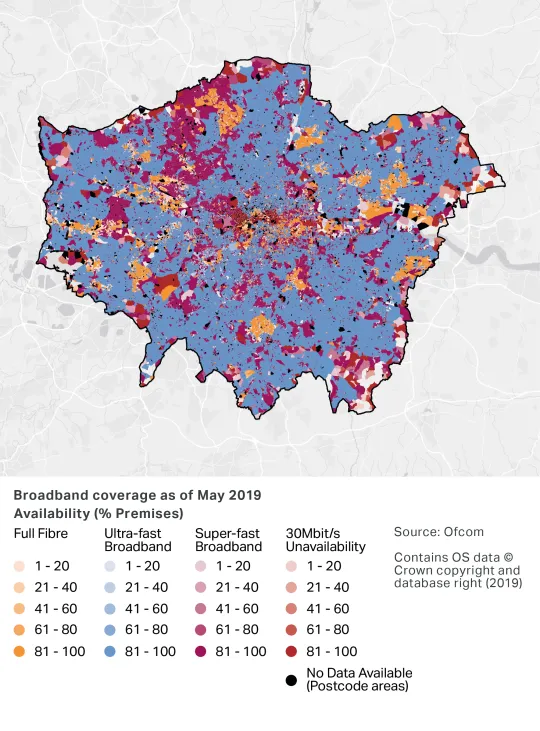

9.6.2 London’s capability in this area is currently limited by a range of issues, including the availability of fibre and the speeds delivered. The industry regulator Ofcom publishes the data on digital connectivity coverage on which Figure 9.5 is based, but there are some limitations to the practicality of the data that is collected. Further work will be done to accurately identify locations in the capital where current connectivity provisions are not suitable for the needs of the area.

9.6.3 Better digital connectivity with a focus on capability, affordability, security, resilience and the provision of appropriate electrical power supply should be promoted across the capital. The specific requirements of business clusters, such as a symmetrical-capable service with the same upload and download speeds, should also be met.

9.6.4 Given the fast pace at which digital technology is changing, a flexible approach to development is needed that supports innovation and choice. Part R1 of the Building Regulations 2010 requires buildings to be equipped with at least 30 MB/s ready in-building physical infrastructure, however new developments using full fibre to the property or other higher-grade infrastructure can achieve connectivity speeds of 1GB/s. Developers should engage early with a range of network operators, to ensure that development proposals are designed to be capable of providing this level of connectivity to all end users. Mechanisms should also be put in place to enable further future infrastructure upgrades. Innovation is driving reductions in the size of infrastructure, with marginal additional unit costs, but greater digital connectivity is needed in more locations.

9.6.5 Development proposals should also demonstrate that mobile connectivity will be available throughout the development and should not have detrimental impacts on the digital connectivity of neighbouring buildings. Early consultation with network operators will help to identify any adverse impact on mobile or wireless connectivity and appropriate measures to avoid/mitigate them.

9.6.6 Access for network operators to rooftops of new developments should be supported where an improvement to the mobile connectivity of the area can be identified. Where possible, other opportunities to secure mobile connectivity improvements should also be sought through new developments, including for example the creative use of the public realm.

9.6.7 For some types of development (such as commercial) specific requirements regarding communications access and security may apply. Data centres, in particular, depend on reliable connectivity and electricity infrastructure. Warehouse-based data centres have emerged as a driver of industrial demand in London over recent years and this will need to be taken into account when assessing demand for industrial land (see Policy E4 Land for industry, logistics and services to support London’s economic function, Policy E5 Strategic Industrial Locations (SIL), Policy E6 Locally Significant Industrial Sites and Policy E7 Industrial intensification, co-location and substitution).

9.6.8 The Mayor will work with network operators, developers, councils and Government to develop guidance and share good practice to increase awareness and capability amongst boroughs and developers of the effective provision of digital connectivity and to support the delivery of policy requirements. The Mayor will also help to identify spatial gaps in connectivity and overcome barriers to delivery to address this form of digital exclusion, in particular through his Connected London work. Boroughs should encourage the delivery of high-quality / world-class digital infrastructure as part of their Development Plans.

9.6.9 Digital connectivity supports smart technologies in terms of the collection, analysis and sharing of data on the performance of the built and natural environment, including for example, water and energy consumption, waste, air quality, noise and congestion. Development should be fitted with smart infrastructure, such as sensors, to enable better collection and monitoring of such data. As digital connectivity and the capability of these sensors improves, and their cost falls, more and better data will become available to improve monitoring of planning agreements and impact assessments, for example related to urban design. Further guidance will be developed to make London a smarter city.

Figure 9.5 - Broadband coverage May 2019

Note for Figure 9.5: For the most up to date broadband coverage and information on broadband connection types please see the Connected London web page

Policy SI 7 Reducing waste and supporting the circular economy

9.7.1 Waste is defined as anything that is discarded. A circular economy is one where materials are retained in use at their highest value for as long as possible and are then re-used or recycled, leaving a minimum of residual waste. London should move to a more circular economy as this will save resources, increase the resource efficiency of London’s businesses, and help to reduce carbon emissions. The successful implementation of circular economy principles will help to reduce the volume of waste that London produces and has to manage. A key way of achieving this will be through incorporating circular economy principles into the design of developments (see also Policy D3 Optimising site capacity through the design-led approach) as well as through Circular Economy Statements for referable applications.

9.7.2 The adoption of circular economy principles for referable applications means creating a built environment where buildings are designed for adaptation, reconstruction and deconstruction. This is to extend the useful life of buildings and allow for the salvage of components and materials for reuse or recycling. Un-used or discarded materials should be brought back to an equal or comparable level of quality and value and reprocessed for their original purpose (e.g. recycling glass back into glass, instead of into aggregate).

9.7.3 To assist with the introduction of Circular Economy principles, the Mayor will be providing further guidance on Circular Economy Statements. Circular Economy Statements are intended to cover the whole life cycle of development. This will apply to referable schemes and be encouraged for other major infrastructure projects within London. Boroughs are encouraged to set lower local thresholds through Development Plans.

9.7.4 In 2015[165] London produced just under 18 million tonnes (mt) of waste, comprising:

• 3.1mt household waste – 17 per cent

• 5.0mt commercial/industrial waste – 28 per cent

• 9.7mt construction, demolition and excavation waste – 54 per cent

9.7.5 Modelling[166] suggests that if London achieves the Mayor’s reduction and recycling targets, it will have sufficient Energy from Waste capacity to manage London’s non-recyclable municipal waste, once the new Edmonton and Beddington Lane facilities are operational.

9.7.6 The London Environment Strategy sets out a pathway to achieving a municipal recycling target of 65 per cent by 2030 and outlines the Mayor’s approach to municipal waste management in detail. This includes London achieving a 50 per cent reduction in food waste and associated packaging waste per person by 2030, and London local authorities needing to provide a minimum level of recycling service, including separate food waste, to residents by 2020. To achieve these recycling targets, it will be important that recycling, storage and collection systems in new developments are appropriately designed. Further detail on how developments should do this is set out in guidance.

9.7.7 Re-use and recycling rates for construction, demolition and excavation waste and material (CD&E) in London is estimated between 50 – 60 per cent[167] for 2015 with some large construction projects including the Olympic Park achieving 85 – 95 per cent recovery rates. The targets for CD&E waste and material are already being set on some projects, but better data (particularly relating to reuse on site) is needed to inform performance. The adoption of circular economy principles in referable applications (and promoted in Local Plans) is expected to help London achieve the CD&E waste and material recovery targets early in the Plan period.

9.7.8 The movement and management of household, commercial and industrial, and construction, demolition and excavation waste will be monitored in collaboration with other stakeholders through available data sets (including the Environment Agency’s Waste Data Interrogator tool and WasteDataFlow) and reporting against commitments in Circular Economy Statements. This will inform reporting on and monitoring of the achievement of the targets set out in this policy, Part A.

9.7.9 Part A4 reflects recent changes to the regulatory regime that mean that the particular characteristics of excavation waste make it difficult to recover. The Mayor will continue to work with stakeholders to understand the implications of this regulatory change and to promote its beneficial use and limit the amount sent to landfill. The best environmental option practicable for the management of excavation material should be used. This could, for example, include using the material as a resource within the construction of the proposed development, or in other local construction projects, or using the material in habitat creation, flood defences or landfill restoration. In line with circular economy principles, the management of excavation waste should be focused on-site or within local projects.

9.7.10 When it is intended to send waste to landfill it will be important to show evidence that the receiving facility has the capacity to deal with waste over the lifetime of the development. This information should be made available to the relevant waste planning authority to help plan for future needs.

Policy SI 8 Waste capacity and net waste self-sufficiency

Table 9.1 - Forecast arisings of household, commercial and industrial waste by borough 2021-2041 (000’s tonnes)

Table 9.2 - Borough-level apportionments of household, commercial and industrial waste 2021-2041 (000’s tonnes)

* Apportionment is per cent share of London’s total waste to be managed by borough

Table 9.3 - Projected net exports of household, commercial and industrial waste from London (000’s tonnes)

Note: 2015 is an actual figure (SLR May 2017), data for 2021, 2026 and 2041 are projections

9.8.1 In 2015, London managed 7.5mt of its own waste and exported 11.4mt of waste. London also imported 3.6mt of waste. This gives London a current waste net self-sufficiency figure of approximately 60 per cent. Around 5mt (49 per cent) of waste exported from London went to the East of England and 4.2mt (42 per cent) to the South East. The bulk of this waste is CD&E waste. Approximately 1.3mt of waste was exported overseas. The term net self-sufficiency is meant to apply to all waste streams, with the exception of excavation waste. The particular characteristics of this waste stream mean that it will be challenging for London to provide either the sites or the level of compensatory provision needed to apply net self-sufficiency to this waste stream.

9.8.2 In 2015, 2.9mt of the waste sent to the East of England went to landfill and 2.2mt went to landfill in the South East. Some 32 per cent of London’s waste that was biodegradable or recyclable was sent to landfill. The Mayor is committed to sending zero biodegradable or recyclable waste to landfill by 2026.

9.8.3 Waste contracts do not recognise administrative boundaries and waste flows across borders. Therefore, sufficient sites should be identified within London to deal with the equivalent of 100 per cent of the waste apportioned to the boroughs as set out in Table 9.2. The Mayor will work with boroughs, the London Waste and Recycling Board, and the London and neighbouring Regional Technical Advisory Bodies to address cross-boundary waste flow issues. Examples of joint working include ongoing updates to the London Waste Map, sharing data derived from Circular Economy Statements, the monitoring of primary waste streams and progress to net self-sufficiency, supporting the Environment Agency’s annual monitoring work, and collaboration on management solutions of waste arisings from London.

9.8.4 Waste is deemed to be managed in London if any of the following activities take place within London:

- waste is used for energy recovery

- the production of solid recovered fuel (SRF), or it is high-quality refuse-derived fuel (RDF) meeting the Defra RDF definition as a minimum[168] which is destined for energy recovery

- it is sorted or bulked for re-use (including repair and re-manufacture) or for recycling (including anaerobic digestion)

- it is reused or recycled (including anaerobic digestion).

9.8.5 Supporting the production of SRF and high-quality RDF feedstock will promote local energy generation and benefit Londoners, improving London’s energy security, helping to achieve regional self-sufficiency and possibly reducing leakage of SRF and RDF overseas. London facilities should produce high-quality waste feedstock with very little recyclable content (i.e. plastics), supporting renewable energy generation.

9.8.6 Table 9.1 shows projected arisings for household, commercial and industrial waste for each borough. National policy guidance requires boroughs to have regard to the waste apportionments set out in the London Plan. The Plan’s waste apportionment model defines the proportion of London’s total household, commercial and industrial waste that each borough should plan for, and these apportionments are set out in Table 9.2. Part B3 requires boroughs to allocate sufficient land (sites and/or areas) and identify waste management facilities to provide the capacity to manage their apportioned tonnages of waste. Boroughs are encouraged to collaborate by pooling their apportionment requirements. Boroughs with a surplus of waste sites should offer to share these sites with those boroughs facing a shortfall in capacity before considering site release.

9.8.7 Boroughs should examine in detail how capacity can be delivered at the local level and demonstrate how this can be provided for through the allocation of sufficient sites and the identification of suitable areas in Development Plans to meet their apportionment, and should aim to meet their waste apportionment as a minimum. It may not always be possible for boroughs to meet their apportionment within their boundaries and in such circumstances boroughs will need to agree the transfer of apportioned waste. Where apportionments are pooled, boroughs must demonstrate how their joint apportionment targets will be met, for example through joint waste Development Plan Documents, joint evidence papers or bilateral agreements.

9.8.8 Mayoral Development Corporations (MDCs) must cooperate with host boroughs to meet identified waste needs; this includes boroughs’ apportionment requirements. This could be widened to cover boroughs in the relevant waste planning group where appropriate. In future iterations of the Plan full consideration will be given to apportioning waste needs to MDCs.

9.8.9 Waste planning authorities and groups should plan to meet the identified waste management needs of their local area and are encouraged to identify suitable additional capacity for waste, including those waste streams not apportioned by the London Plan, where practicable. This could include, waste transfer sites, new sites managing construction, demolition and excavation waste, or the reconfiguration and intensification of existing uses that increase management capacity.

9.8.10 Plans or agreements safeguarding waste sites should take a flexible approach. They should be regularly reviewed and updated to take account of development that may lead to the integration of waste sites or appropriate relocation of lost waste sites. Waste plans should be responsive to strategic opportunities across borough and joint waste planning boundaries for optimising capacity on existing waste sites, or that help to unlock investment in developing new waste sites. Where a waste site may be lost, compensatory capacity should first be explored within the borough. In cases where this can’t be provided, and suitable capacity is found in another borough, the receiving borough or joint waste planning group is encouraged to take on the apportionment and include it as part of their Development Plan.

9.8.11 Land in Strategic Industrial Locations will provide the main opportunities for locating waste treatment facilities. Existing waste management sites should be clearly identified and safeguarded for waste use. Boroughs should also look to Locally Significant Industrial Sites and intensification of existing waste management sites. Large-scale redevelopment opportunities and redevelopment proposals should incorporate waste management facilities within them. The London Waste Map[169] shows the locations of London’s permitted waste facilities and sites that may be suitable for waste facility location.

9.8.12 As noted above, waste flows across boundaries and London exported 3.4mt of household, commercial and industrial waste in 2015. To meet the Mayor’s policy commitment of net self-sufficiency by 2026 there needs to be a reduction in exports or an increase in imports in the lead up to 2026. Table 9.3 is included to help neighbouring authorities plan for London’s expected household, commercial and industrial waste exports.

9.8.13 Tables 9.1, 9.2 and 9.3 only refer to household, commercial and industrial waste, not construction, demolition and excavation waste. As the reliability of CD&E waste data is low, apportionments for this waste stream are not set out. For a fuller discussion of the issues around CD&E waste data see paragraph 9.7.7 and the SLR consulting report (task 2) (May 2017).

9.8.14 To support the shift towards a low-carbon circular economy, all facilities generating energy from waste should meet, or demonstrate that they can meet in future, a measure of minimum greenhouse gas performance known as the carbon intensity floor (CIF). The CIF is set at 400g of CO2 equivalent generated per kilowatt hour (kwh) of electricity generated. The GLA’s free on-line ready reckoner tool can assist boroughs and applicants in measuring and determining performance against the CIF.[170] Achieving the CIF effectively rules out traditional mass burn incineration techniques generating electricity only. Instead, it supports techniques where both heat and power generated are used, and technologies are able to achieve high efficiencies, such as when linked with gas engines and hydrogen fuel cells. More information on how the CIF has been developed and how to meet it can be found in the London Environment Strategy.

9.8.15 Waste to energy facilities should be equipped with a heat off-take from the outset such that a future heat demand can be supplied without the need to modify the heat producing plant in any way or entail its unplanned shut-down. It should be demonstrated that capacity of the heat off-take meets the CIF at 100 per cent heat supply. In order to ensure it remains relevant, the CIF level will be kept under review.

9.8.16 Examples of the ‘demonstrable steps’ required under Part E3 are:

-

a commitment to source truly residual waste – waste with as little recyclable material as possible

-

a commitment (via a Section 106 obligation) to deliver the necessary means for infrastructure to meet the minimum CO2 standard, for example investment in the development of a heat distribution network to the site boundary, or technology modifications that improve plant efficiency

-

an agreed timeframe (via a Section 106 agreement) as to when proposed measures will be delivered

-

the establishment of a working group to progress the agreed steps and monitor and report performance to the consenting authority.

9.8.17 To assist in the delivery of ‘demonstrable steps’ the GLA can help to advise on heat take-off opportunities for waste to energy projects, particularly where these are linked to GLA supported energy masterplans.

9.8.18 In 2015 around 324,000 tonnes of hazardous waste was produced in London. Hazardous waste makes up a component of all waste streams and is included in the apportionments for household, commercial and industrial waste set out in Table 9.2. London sends small amounts of hazardous waste to landfill outside of London, approximately three per cent of the national total. The amount of such waste produced has continued to grow in the short and medium-term. Without sustained action, there remains the risk of a major shortfall in our capacity to treat and dispose of hazardous waste safely. This could lead to storage problems, illegal disposal (including fly tipping) and rising public concern about health and environmental impacts. There is therefore a need to continue to identify hazardous waste capacity for London. The main requirement is for sites for regional facilities to be identified. Boroughs will need to work with neighbouring authorities to consider the necessary facilities when planning for their hazardous waste.

9.8.19 Waste processing facilities should be well designed. They should respect context, not be visually overbearing and should contribute to the local economy as a source of new products and new jobs. They should be developed and designed in consultation with local communities, taking account of health and safety within the facility, the site and adjoining neighbourhoods. Developments supporting circular economy outcomes such as re-use, repair and re-manufacture, will be encouraged. Where movement of waste is required, priority should be given to facilities for movement by river or rail. Opportunities for combined heat, power and cooling should be taken wherever possible. Although no further landfill proposals in London are identified or anticipated within the Plan period, if proposals do come forward for new or extended landfill capacity or for land-raising, boroughs should ensure that the resultant void-space has regard to the London Environment Strategy.

9.8.20 Following the Agent of Change principle, developments adjacent to waste management sites should be designed to minimise the potential for disturbance and conflicts of use. Developers should refer to the London Waste and Recycling Board’s design guide for ensuring adequate and easily accessible storage space for high-rise developments, see Part E of Policy D6 Housing quality and standards.

Policy SI 9 Safeguarded waste sites

9.9.1 London has approximately 500 waste sites, defined as land with planning permission for a waste use or a permit from the Environment Agency for a waste use. This applies to land used for any waste stream. These sites cover a wide range of waste activities and perform a valuable service to London, its people and economy.

9.9.2 Any proposed release of current waste sites or those identified for future waste management capacity should be part of a plan-led process, rather than done on an ad-hoc basis. Waste sites should only be released to other land uses where waste processing capacity is re-provided elsewhere within London, based on the maximum achievable throughput of the site proposed to be lost. When assessing the throughput of a site, the maximum throughput achieved over the last five years should be used; where this is not available potential capacity of the site should be appropriately assessed.

9.9.3 Policy SI 8 Waste capacity and net waste self-sufficiency promotes capacity increases at waste sites where appropriate to maximise their use. If such increases are implemented over the Plan period, it may be possible to justify the release of waste sites if it can be demonstrated that there is sufficient capacity available elsewhere in London at appropriate sites over the Plan period to meet apportionment and that the target of achieving net self-sufficiency is not compromised. In such cases, sites could be released for other land uses.

Policy SI 10 Aggregates

9.10.1 London needs a reliable supply of construction materials to support continued growth. National planning policy requires Mineral Planning Authorities to maintain a steady and adequate supply of aggregates. These include land-won sand and gravel, crushed rock, marine sand and gravel, recycled materials and secondary aggregates created from construction, demolition and excavation (CD&E) and industrial waste. Most aggregates used in the capital come from outside London, including marine sand and gravel and land-won aggregates, principally crushed rock from other regions. There are relatively small resources of workable land-won sand and gravel in London.

9.10.2 A realistic landbank (i.e. seven years’ supply) of at least 5 million tonnes of land-won aggregates for London throughout the Plan period has been apportioned to boroughs as set out in this policy. There remains some potential for extraction beyond the four boroughs identified, including within the Lee Valley. Boroughs with aggregates resources should consider extraction opportunities when preparing Development Plans.

9.10.3 Those boroughs with an apportionment should plan to meet their landbank target and plan for the steady and adequate supply of minerals through the identification of specific sites where viable resources are known to exist, preferred areas where known resources are likely to get planning permission, and areas of search where mineral resources might reasonably be anticipated.

9.10.4 Aggregates are bulky materials so Development Plans should maximise their use and re-use and minimise their movement, especially by road. The objective of proximity dictates that the best option is the use of local materials where feasible. The re-use/recycling of building materials and aggregates is a significant and well established component of the circular economy advocated in Policy SI 7 Reducing waste and supporting the circular economy and reduces the demand for natural materials.

9.10.5 Boroughs should identify and safeguard existing, planned and potential sites for aggregate extraction, transportation, processing and manufacture – and recognise where there may be benefits in their co-location. Existing and future wharf capacity is essential, especially for transporting marine-dredged aggregates, and should be protected in accordance with Policy SI 15 Water transport. Equally important are railway depots for importing crushed rock from other parts of the UK. Railheads are vital to the sustainable movement of aggregates and boroughs should safeguard these sites in line with Policy T7 Deliveries, Servicing and Construction. Boroughs should also safeguard sites for the production and distribution of aggregate products.

9.10.6 Development proposals and planning decisions should ensure that impacts to environment, heritage and amenity values are considered, including the cumulative effects of multiple impacts from individual sites and/or a number of sites in a locality. Principal issues include noise, dust, air quality, lighting, archaeological and heritage features, traffic, land contamination, impacts to surface and ground water and land stability.

9.10.7 Sites for depots may be particularly appropriate in preferred industrial locations and other employment areas. Boroughs should examine the feasibility of using quarries as CD&E recycling sites once mineral extraction has finished.

9.10.8 Mineral Planning Authorities are required to prepare an annual Local Aggregates Assessment (LAA). The Mayor will work with boroughs and the London Aggregates Working Party to explore options for the preparation of joint LAAs in the future.

Policy SI 11 Hydraulic fracturing (Fracking)

9.11.1 In line with the Plan’s policy approach to energy efficiency, renewable energy, climate change, air quality, and water resources, the Mayor does not support fracking in London.

9.11.2 The British Geological Survey concluded in a 2014 report for the Department of Energy and Climate Change that “there is no significant Jurassic shale gas potential in the Weald Basin”.[171] It is highly unlikely that there is any site that is geologically suitable for a fracking development in London.

9.11.3 Should any London fracking proposal come forward there is a high probability that it would be located on Green Belt or Metropolitan Open Land. Furthermore, London and the south east of England are seriously water-stressed areas. Fracking operations not only use large amounts of water but also presents risks of potential contamination, presenting significant risks to London.

9.11.4 In addition to avoiding or mitigating adverse construction and operational impacts (noise, dust, visual intrusion, vehicle movements and lighting, on both the natural and built environment, including air quality and the water environment), any fracking proposal would need to take full account, where relevant, of the following environmental constraints:

- Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest

- Groundwater Source Protection Zone 1

- Special Protection Areas (adopted or candidate)

- Special Areas of Conservation (adopted or candidate)

- Sites of Metropolitan Importance for Nature Conservation

- groundwater or surface water

9.11.5 The United Kingdom Onshore Oil and Gas Group (UKOOG), which represents the industry, has established a Community Engagement Charter for new onshore oil and gas proposals.[172] The Charter sets out a number of commitments for operators which includes engagement with local communities at each of the three main stages of operations (exploration, appraisal and production). Where any proposals for fracking to come forward, applicants who are members of UKOOG would be expected to comply with these commitments.

Policy SI 12 Flood risk management

9.12.1 In London, the boroughs are Lead Local Flood Authorities (LLFAs) and are responsible, in particular, for local surface water flood risk management and for maintaining a flood risk management assets register. They produce Local Flood Risk Management Strategies. LLFAs should cooperate on strategic and cross-boundary issues.

9.12.2 The Regional Flood Risk Appraisal (RFRA) considers all sources of flood risk including tidal, fluvial, surface water, sewer, groundwater and reservoir flooding and has been updated in collaboration with the Environment Agency. The RFRA provides a spatial analysis of flood risk including consideration of risks at major growth locations such as Opportunity Areas and Town Centres and key infrastructure assets. The Government’s updated allowances for climate change are reflected in the expected sea level rise and increased flood risks considered in the RFRA. The updated allowances consider the lifetime, vulnerability and location of a development.

9.12.3 The Thames Estuary 2100 Plan (TE2100), published by the Environment Agency, and endorsed by Government, focuses on a partnership approach to tidal flood risk management. It requires the ability to maintain and raise some tidal walls and embankments. The Environment Agency estimates that a new Thames Barrier is likely to be required towards the end of the century. Potential sites will be needed in Kent and/or Essex requiring close partnership working with the relevant local authorities.

9.12.4 The concept of Local Authorities producing Riverside Strategies was introduced through the TE2100 Plan to improve flood risk management in the vicinity of the river, create better access to and along the riverside, and improve the riverside environment. The Mayor will support these strategies.

9.12.5 The Environment Agency’s Thames River Basin District Flood Risk Management Plan is part of a collaborative and integrated approach to catchment planning for water. Measures to address flood risk should be integral to development proposals and considered early in the design process. This will ensure they provide adequate protection, do not compromise good design, do not shift vulnerabilities elsewhere, and are cost-effective. Natural flood risk management in the upper river catchment areas can also help to reduce risk lower in the catchments. Making space for water when considering development proposals is particularly important where there is significant exposure to flood risk along tributaries and at the tidal-fluvial interface. The Flood Risk Management Plan should inform the boroughs’ Strategic Flood Risk Assessments.

9.12.6 In terms of mitigating residual risk, it is important that a strategy for resistance and then resilience including safe evacuation and quick recovery to address such risks is in place; this is also the case for utility services. In the case of a severe flood, especially a tidal flood, many thousands of properties could be affected. This will make rescue and the provision of temporary accommodation challenging. Designing buildings such that people can remain within them and be safe and comfortable in the unlikely event of such a flood, will improve London’s resilience to such an event.

Policy SI 13 Sustainable drainage

9.13.1 London is at particular risk from surface water flooding, mainly due to the large extent of impermeable surfaces. Lead Local Flood Authorities have responsibility for managing surface water drainage through the planning system, as well as ensuring that appropriate maintenance arrangements are put in place. Local Flood Risk Management Strategies and Surface Water Management Plans should ensure they address flooding from multiple sources including surface water, groundwater and small watercourses that occurs as a result of heavy rainfall.

9.13.2 Development proposals should aim to get as close to greenfield run-off rates[173] as possible depending on site conditions. The well-established drainage hierarchy set out in this policy helps to reduce the rate and volume of surface water run-off. Rainwater should be managed as close to the top of the hierarchy as possible. There should be a preference for green over grey features, and drainage by gravity over pumped systems. A blue roof is an attenuation tank at roof or podium level; the combination of a blue and green roof is particularly beneficial, as the attenuated water is used to irrigate the green roof.

9.13.3 For many sites, it may be appropriate to use more than one form of drainage, for example a proportion of rainwater can be managed by more sustainable methods, with residual rainwater managed lower down the hierarchy. In some cases, direct discharge into the watercourse is an appropriate approach, for example rainwater discharge into the tidal Thames or a dock. This should include suitable pollution prevention filtering measures, ideally by using soft engineering or green infrastructure. In addition, if direct discharge is to a watercourse where the outfall is likely to be affected by tide-locking, suitable storage should be designed into the system. However, in other cases direct discharge will not be appropriate, for example discharge into a small stream at the headwaters of a catchment, which may cause flooding. This will need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis, taking into account the location, scale and quality of the discharge and the receiving watercourse. The maintenance of identified drainage measures should also be considered in development proposals.

9.13.4 The London Sustainable Drainage Action Plan complements this policy. It contains a series of actions to make the drainage system work in a more natural way with a particular emphasis on retrofitting.

Policy SI 14 Waterways – strategic role

9.14.1 The term ‘waterways’ does not only refer to the River Thames, its tributary rivers and canals, but also to other water spaces including docks, lakes and reservoirs. This network of linked waterways – also known as the Blue Ribbon Network – is of strategic importance for London. Every London borough contains some waterways – 17 border the Thames and 15 contain canals (see Figure 9.6).

9.14.2 London’s waterways are multifunctional assets. They provide transport and recreation corridors; green infrastructure; a series of diverse and important habitats; a unique backdrop for important heritage assets, including World Heritage Sites, landscapes, views, cultural and community activities; as well as drainage, flood and water management and urban cooling functions. As such, they provide environmental, economic and health and wellbeing benefits for Londoners and play a key role in place making. They also provide a home for Londoners living on boats. The waterways are protected and their water-related use – in particular safe and sustainable passenger and freight transport, tourism, cultural, community and recreational activities, as well as biodiversity – is promoted. Many of these functions are also supported by boroughs’ local Riverside Strategies, the Environment Agency’s Thames River Basin Management Plan and the Port of London Authority’s Vision for the Thames. In addition to the Thames, other water spaces, and in particular canals, have a distinct value and significance for London and Londoners.

Figure 9.6 - London’s Network of Waterways (the Blue Ribbon Network)

9.14.3 The Thames and London Waterways Forum[174] has been established jointly by the GLA, TfL and the Port of London Authority to address waterways priorities set out in this Plan, the Mayor’s Transport Strategy, the London Environment Strategy and the Port of London Authority’s Vision for the Thames.

9.14.4 As London’s waterways cross borough boundaries, it is important to plan for their management strategically. Boroughs are encouraged to work together to develop appropriate policies or joint area-based waterways strategies to maximise the multifunctional benefits waterways provide.

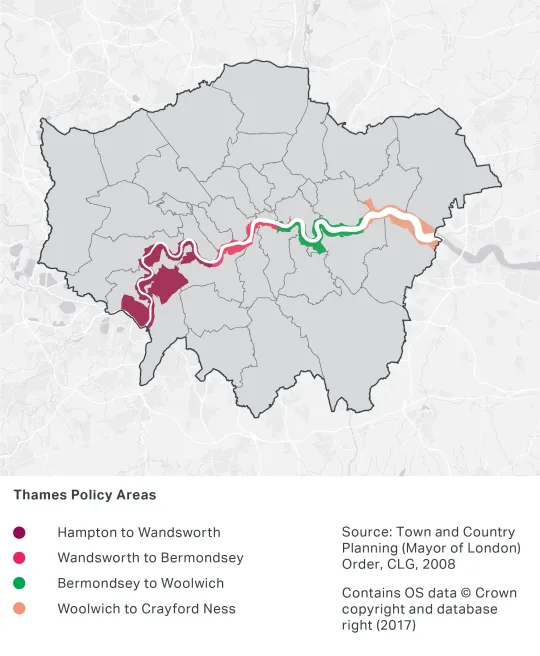

9.14.5 The River Thames is a strategically-important and iconic feature of London. It is a focal point for London’s identity reflecting its heritage, natural and landscape values as well as cultural opportunities. Its character changes on its way through London. Where Thames Policy Areas (TPAs) are not defined in Development Plans, the boundaries defined in Figure 9.7 apply. Within TPAs, lower-height thresholds for referable planning applications apply (25m compared to 30m elsewhere).

9.14.6 In defining TPA boundaries, boroughs should work collaboratively and have regard to the following:

- proximity to the Thames

- clear visual links between areas, buildings and the river

- specific geographical features such as main roads, railway lines and hedges

- the whole curtilage of properties or sites adjacent to the Thames

- areas and buildings whose functions relate or link to the Thames

- areas and buildings that have an historic, archaeological or cultural association with the Thames

- consistent boundaries with neighbouring authorities.

9.14.7 Joint Thames Strategies should specifically identify and address deficiencies in: water-based passenger, tourism and freight transport; sport, leisure and mooring facilities; marine support infrastructure; and inclusive access and safety provision. Thames Strategies are in place for Hampton–Kew, Kew-Chelsea and East (of Tower Bridge). No joint strategy currently exists for the central section of the Thames (Chelsea-Tower Bridge).

Figure 9.7 - Thames Policy Areas